Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)/Saving Catholicism

Saving France. Or Saving Catholicism through France?

This page will review the political history of Joan's time and build the context for her larger missions of saving France, as she herself stated, and, by extension, as I will argue, saving Roman Catholicism.

See Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle) for the prior discussion to this page.

These pages present a Catholic view of Saint Joan that is consistent with the history. It reviews the facts of the life and accomplishments of Saint Joan of Arc, as well as their historical context. It offers commentary and criticism of historical and academic views of Joan, especially as regards the secularization and ideological contortions of her legacy. Presented here, as well, is the theory that Joan's mission was not to save France so much as to save Roman Catholicism.

And, these pages assume everything that Joan testified to was real, not just to her, but objectively real to all.

** page under construction **

Related pages:

- Joan of Arc Timeline

- Kings of France and England

- Popes and antipopes

- Saint Joan of Arc Glossary for names, places & terms, as well as a flow chart of the lineage of French Kings (which can otherwise be confusing)

Here for Saint Joan of Arc category list of related pages

Joan's mission: to save France -- or Catholicism?

I have a theory. I developed it before I knew anything about Saint Joan other than she led the French to defeat the English and was burnt at the stake for it all. As I have learned more about her, the theory makes more and more sense that her mission was to save Catholicism, not France.

What is "France"?

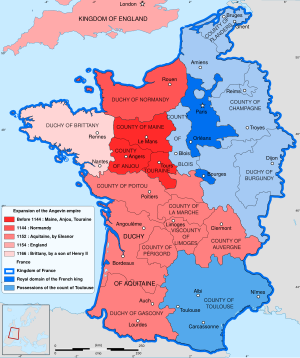

France, as we know it, doesn't really become "France" until Philip II, but not with national integrity and full identity until Joan of Arc. It's all rather complicated, but following the Norman Invasion of England in 1066, the Normans controlled the north of France and England. After series of power grabs, political marriages, dynastic divisions, and armed contests, by the 12th century, Henry II, who spoke French,[1] had taken over a large part of western France, creating the Angevin Empire, which lasted until the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, in which the French defeated an English and a European coalition that opposed Philip II's conquests of France. As a result, English King John was severely weakened and was forced into signing the Magna Charta and Philip II consolidated France, effectively creating modern France.[2] History weaves complex, indeed.

In 1328, a succession crisis arose at the death of Charles IV of France, whose closest heir was his nephew Edward III of England. Eddie, of course, claimed the throne. Rejected by the French nobles, Ed cut a deal with the Flemish who endorsed him as King of France, everything to do, of course, with the economic binds between English sheep and Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres woolen factories. In the 1340s, Eddie put together an invasion force and in 1346 took the northern city of Caen and then thoroughly humiliated the French at Crécy, largely because the French fought the same war as at Bouvines, with heavy armor, while the English brought in the next thing, the longbow, which could be fired in rapid succession (unlike the French crossbows) and could also pierce armor from distance.

It gets complicated, what with English victories in the southwest of France (remnants of the Angevin Empire) and a series of crises in France, which led to the coronation of Charles VI, "Charles the Mad," renowned today as the crazy king who thought he was made of glass.[3] In 1420, Charles disinherited his own son, who would become the "Dauphin" (claimant to the throne of France) whom Saint Joan herself, basically, crowned as Charles VII[4], appoints the English King Henry V, who took advantage of the chaos in France and crippled the French army at Agincourt in 1415. After this, the English and their French allies ally, the Count of Burgundy, give or take some stumbles, ally for mutual benefit to take over France.

Most people would look upon the Hundred Years War as, and the language of the day, a war between the English and the French. Indeed, the French called their enemy the English, and the English called their enemy the French. In more than a small way they were all French, which is why the English king claimed the French throne.

In my theory, had the "English," whose rulers spoke French at home, won and reclaimed France on top of England, then both England and France, a hundred years later, would have under Henry VIII left the Catholic church. Sure, lots of conditions may have prevented that, but we can draw a straight line from the Church of England to the Church of England/France. This would not have pleased God.

Whatever the value of my theory that God meant to keep France Catholic, I am intrigued by this excerpt from Mark Twain's account of the trial of St. Joan:

And now, by order of Cauchon, an ecclesiastic named Nicholas Midi preached a sermon, wherein he explained that when a branch of the vine — which is the Church — becomes diseased and corrupt, it must be cut away or it will corrupt and destroy the whole vine.

Whereas the English partisan, Father Midi, saw the destruction of Joan the pruning of a dead branch of the Church (the vine, as Twain correctly explains), by cutting her off, he and Bishop Cauchon were instead pruning themselves from the vine of France. The dead vine cut off was England.

There is an additional

> Henry VIII

> to save France -- from what, the English who were French?

Saving Catholicism

Saint Joan saved France, yes. But she more importantly saved Catholic France and thereby Catholicism itself, as had France fallen to what was to become English Anglican and Protestant rule, so likely would have fallen the rest of Catholic western Europe.[5]

When, just before the Battle of Orléans, Joan warned the French commander there, the Bastard of Orléans[6], to quit futzing around and get busy so she could save France, she told him that it wasn't about her, it was about God:

This help comes not for love of me but from God Himself, who at the prayer of St. Louis and of St. Charlemagne has had pity on the city of Orléans.

Huh, Saints Louis and Charlemagne?[7]

Intercession of Saints Charlemagne & Louis

When Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Imperator Romanorum (emperor of the Romans) in 800, he crowned the Frankish king Charles (Carolus, Karlus) king of western Christianity, creating what would later become the Holy Roman Empire. In submitting as vassal to the Pope, Charlemagne legitimized both his own rule and that of Roman Catholicism across his empire.[8] Among the religious legacies of Charlemagne was the practice of the laity of memorizing and reciting the Our Father prayer and the Apostle's Creed with the filioque[9] and the traditional singing of "Noel" at coronations in honor of Charlemagne's coronation by the Pope on Christmas Day.

Saint Louis was the French king Louis IX (reigned 1226-1270). Crowned at Rheims,[10] he ruled as a devout and pious Christian to such extent that he was canonized not long after his death. Louis' reign was marked by consistent protection of the clergy and Church from secular rule and strict allegiance to the papacy.[11] He is considered the quintessential "Christian" -- but more correctly, Catholic, king.[12] As for historical context regarding Joan, in 1259 he consolidated French rule over Normandy at the Treaty of Paris with English King Henry III. Some historians attribute Louis' concession of Duchy of Guyenne to the English under French vassalage to the outbreak of the Hundred Years War, but there is no direct causality to make that connection, and even if there was any unfinished business Louis preferred settlement over continued war.[13]

If Joan's mission was to save France, Philip II (reigned 1165-1223) would have been the better intercessor, not Charlemagne or his grandson St. Louis, for Charlemagne's empire extended across Germany, and while Saint Louis extended French sovereignty, it was Philip who created the modern France that Joan defended.[14] Philip, in fact was the first to declare himself "King of France." Now, Philip was no Saint, as they say, so in Saints Charlemagne and Louis IX, perhaps Joan was appealing more to the Roman Catholic France than to the territorial one. Or, in that Joan's exhortation to the Bastard was about Orléans and not France, perhaps "the prayer of St. Louis and of St. Charlemagne" was just for the city. But Orléans was the key to it all, as so went Orléans, so went France -- and, ultimately, French Catholicism.

The French King Charles V (reigned 1364-1380), who considered himself the fifth "Charles" of France,[15] promoted veneration of Charlemagne, including to dedicate a chapel to him at St. Denis with an elaborate reliquary, which treated him like a saint. The city of Rheims maintained a cult of Charlemagne and actively supported his canonization by the antipope Paschall III in 1165.[16]

>> fix < here? >> After resolving the 12th century schism of antipopes aligned with the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I ("Barbarossa"), Pope Alexander III annulled their papal acts, which included the canonization of Charlemagne.[17]

We can't say that it was of regional tradition or a remnant of the revoked canonization that Joan invoked, but we do know that when referring to "Saint Charlemagne" prior to Orléans, Joan was under the guidance of her voices. She invoked their names for a reason.

The Babylonian Captivity

Joan herself was born amidst an ongoing papal schism. When she was five years old, the "Western Schism"[18] of 1378 was finally settled with a consensus selection at Rome of Pope Martin V, although two rival claims persisted.[19] However, the antipope from Avignon, Benedict XIII, refused to concede, and he moved to Spain under the protection of the King of Aragon who used his presence there for leverage on other issues with Rome. It was Benedict's successor, the antipope Clement VIII who twelve years later finally gave up on the project on July 26, 1429 when the King of Aragon withdrew his support for him.[20] Note the date: Joan's triumph at Orléans was in May and the coronation of Charles VII at Rheims occurred on July 17. There is an interesting parallel to Joan in the Schism itself, precipitated by Pope Gregory XI's move from Avignon to Rome in 1377, ending the uncontested "Avignon Papacy" but prompting the schismatic, French-backed papacy back at Avignon. Known as the "Babylonian Captivity," the official Avignon papacy lasted through seven Popes across sixty-seven years. We see in these events an inversion of antagonists from that of Joan's day: Where the English provoked God's wrath in the Hundred Year's War, the French caught themselves up in less-than-holy entanglements during the Avignon period, which ended only after the intervention of another female Saint, Catherine of Sienna.

In 1289, Pope Pope Nicholas IV allowed the French King Philip IV to collect a one-time Crusades tithe from certain territories under Rudolf of Habsburg (who was not happy about it) in order to pay down Philip's war debts. With the costs of ongoing wars with Aragon, England and Flanders, Philip was up to his ears in financial gamesmanship, including debasement of the currency, bans on export of bullion, and seizure of the assets of Lombard merchants. In 1296, he imposed a severe tax upon Church lands and clergy in France, which didn't go over well with Rome. Pope Boniface VIII responded with the first of three Papal Bulls aimed at Philip denying his right to tax the Church without papal permission and generally asserting papal over secular authority.

The Pope compromised by allowing such a tax for emergencies only, and Philip went ahead anyway with at least some. Things escalated from there, with Philip prosecuting clerical agents from Rome in royal courts and the Pope issuing a wonderfully named Bull, Ausculta Fili ("Listen, My Son"), which Philip not only ignored but had burned in public. Boniface called the French Bishops to Rome, the assembly of which Philip preempted by convening the first Estates General in France, a council with representatives from the nobility, clergy, and commons. Boniface issued another Bull asserting Papal authority and excommunicated anyone, ahem, who prevented clerics from traveling to Rome. Philip did the obvious thing and sent a small army of sixty troops to arrest the Pope and force his abdication. The soldiers stormed the papal estate at Anagni, south of Rome, and held him for three days until residents retaliated and rescued the Pope from the French.[21] Now Philip got an excommunication directed at him personally. Boniface, though, likely from injuries or trauma suffered from the attack, and possibly from poisoning by the French, died shortly after.

Philip's excursion to Anagni put pressure on the subsequent Papal conclave to avoid further antagonism with him. The next Pope, Benedict XI, rescinded the excommunication but not that of Philip's minister who led the attack on Boniface[22], thus leaving the conflict unsettled. Benedict, though, died within a year,[23] and after a year-long impasse between French and Italian Cardinals at the ensuing Conclave, Philip had his way with selection of the Frenchman, Raymond Bertrand de Got, as Pope Clement V. Clement basically did Philip's will, which included effective rescindment of Boniface's Bulls, a posthumous inquisition into Boniface in order to discredit him (which failed), sanction of Philip's arrest of the Knights Templar, and, most importantly, move of the entire Papal court to Avignon in the south of France. This was 1309.

Return from exile: Gregory XI & Saint Catherine of Sienna

Philip's capture of the Papacy worked well for him but no so much for the Church, which, bound to French dominance, lost its legitimacy elsewhere. At first the old enemies of Philip, England and Aragon, found it convenient not to have to deal with the Italians in Rome so did not object. However, a succession crisis among Philip IV's heirs led to the English claims on the French throne and outbreak of the Hundred Years War, over which the Avignon Papacy, while maintaining neutrality and assisting in treaty settlements, leaned towards the French side. So when Gregory XI moved the papacy back to Rome in 1376, the French were furious while the English could sit on their hands and shrug, "oh well." No objection them. And no objection, either, from the Holy Roman Emperor, whose brand was quite literally diluted by the move from Rome to Avignon.

Shortly after arriving at Rome, Gregory died. Under the threats from a Roman mob to appoint an Italian, i.e., not a French pope, and with disunity and among the French faction, as well as absence of some of the French Cardinals, the Conclave compromised on a bishop from Naples[24], who became Urban VI.

Two years later, with Urban refusing to return to Avignon, the French Cardinals held their own conclave south of Rome at Anagni, at invitation of the Count thereof, Onorato Caetani, who was angry at Urban VI for removing him from lands appointed to him by Gregory XI.[25] The French Bishops selected a rather complicated man, Robert of Geneva, son of the Count of Geneva, who had studied at the Sorbonne, held a rectory in England, and earned the nickname "Butcher of Cesena" for authorizing the massacre of three to eight thousand people for the town's participation in a 1377 rebellion against the Papal States (lands directly ruled by the Pope). Now Clement VII, Caetani tried to set up shop in Naples, but was chased out of town by a mob who supported the Roman Pope, shouting, "Death to the Antichrist!" King Charles V of France, who certainly had a say in Caetani's selection, welcomed him back to Avignon as Clement VII and gathered support from various regions and countries who, for whatever reason, preferred France over England, such as the Scottish who went with whatever the English did not.

This time period crosses with that of Saint Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373) who was terribly upset at the Avignon papacy, but whose pleadings to the Church to return to Rome were ignored. In 1350, Bridget sought papal authorization for her order, the Bridgettines, but she refused to go to Avignon, and went to Rome instead where she awaited the Pope's return -- which occurred finally in 1367 when the Avignon Pope Urban V visited Rome as a symbolic gesture of a permanent return. In Rome, he ran the Holy See from the Vatican but ran into various problems with local lords who had gotten used to having things their way. Along with rebellions within the Papal States (taking advantage of the absence of Rome), Urban faced trouble with the bishops back at Avignon who demanded his return. He did grant Saint Bridget her order in 1370, but as he prepared that year to return to Avignon, Saint Bridget told him that if he left Rome he would die. He did, and three and a half months later he died.

Urban's successor, Pierre Roger de Beaufort[26], who became Gregory XI, had witnessed in person Bridget's prophesy to Urban V[27], which may have, one can imagine, at least been in the back of his mind when he privately vowed before God to return the papacy to Rome should he be selected as Pope. Whatever the intention, for the first years of his papacy there were plenty of fires to put out (or try) and reforms to institute, including, interestingly, his 1373 règle d'idiom, which instructed clergy to speak the local vernacular to their flocks outside of the liturgy, came well before the proto-Protestant heretic John Wycliffe translated the Bible into English.[28] Gregory's attempts to reconcile the kings of France and England failed.

The Avignon papacy was not tenable. And no matter how you look at it, Saint Peter died at Rome and not Avignon. Gregory XI seemed to think so, anyway, but he only acted on the conviction at the insistence of Saint Catherine of Sienna (1347-1380). Saint Catherine had picked up where Saint Bridget had left off,[29] dictating a series of letters to the Pope commanding him, among things, to return to Rome and in language Gregory characterized as having an “intolerably dictatorial tone, a little sweetened with expressions of her perfect Christian deference.”[30] Not sure if it's Catherine so much as Gregory not wanting to hear it.[31] For example, she wrote,

I have prayed, and shall pray, sweet and good Jesus that He free you from all servile fear, and that holy fear alone remain. May ardor of charity be in you, in such wise as shall prevent you from hearing the voice of incarnate demons, and heeding the counsel of perverse counselors, settled in self-love, who, as I understand, want to alarm you, so as to prevent your return, saying, “You will die.” Up, father, like a man! For I tell you that you have no need to fear.[32]

In 1376, Catherine traveled to Avignon on behalf of the Republic of Florence to negotiate a peace with the Papal States.[33] She failed at the immediate mission[34] but through a divine inspiration won a far more important one: when they met, she told him that she knew of his private vow to return the papacy to Rome.[35] He so decided, but wavered in face of strenuous French objections. When Catherine heard of the indecision, she wrote,

I beg of you, on behalf of Christ crucified, that you be not a timorous child but manly. Open your mouth and swallow down the bitter for the sweet.

In January of 1377, Gregory moved the papacy back to Rome. He soon after died, and his successor Urban VI refused to return to Avignon, where the French bishops held their own conclave and selected Clement VII, the first antipope of the "Western Schism" that would last almost seventy years, and that would lay the ground for the Martin Luther and the protestant schisms that followed.

Saint Joan questioned on the Schism

By the time of Joan's Trial of Condemnation in 1431, the Western Schism had been officially settled, but the Court tried to use her views on it to discredit her or trip her up. Perhaps thinking that Joan would take the French view of things, she was asked,

What do you say of our Lord the Pope? and whom do you believe to be the true Pope?

To which Joan gave one or her sublime replies,

“Are there two of them?”

Having that one swatted down, the court continued,

Did you not receive a letter from the Count d’Armagnac, asking you which of the three Pontiffs he ought to obey?

Joan replied,

The Count did in fact write to me on this subject. I replied, among other things, that when I should be at rest, in Paris or elsewhere, I would give him an answer. I was just at that moment mounting my horse when I sent this reply.

It's a classic legal maneuver they tried ot pull on her, to lead a witness into a statement, then throw out contrary evidence, in this case, her exchange with the Count. But there was no deceit in Joan, who's testimony was entirely consistent with the evidence. What had happened is that in July 1429, Jean IV, the Count d'Armagnac, himself allied with the English, sent a letter to Joan asking her to clarify the ongoing situation. They got the copies from him. Nevertheless, we have to assume the sincerity of the original letter, as well as the Count's intent: he genuinely thought Joan would provide divine guidance on the situation. As read to the Court at Tours two years later,

My very dear Lady—I humbly commend myself to you, and pray, for God’s sake, that, considering the divisions which are at this present time in the Holy Church Universal on the question of the Popes, for there are now three contending for the Papacy—one residing at Rome, calling himself Martin V., whom all Christian Kings obey; another, living at Paniscole, in the Kingdom of Valence, who calls himself Clement VII[36].; the third, no one knows where he lives, unless it be the Cardinal Saint Etienne and some few people with him, but he calls himself Pope Benedict XIV. The first, who styles himself Pope Martin, was elected at Constance with the consent of all Christian nations; he who is called Clement was elected at Paniscole, after the death of Pope Benedict XIII., by three of his Cardinals; the third, who dubs himself Benedict XIV., was elected secretly at Paniscole, even by the Cardinal Saint Etienne. You will have the goodness to pray Our Saviour Jesus Christ that by His infinite Mercy He may by you declare to us which of the three named is Pope in truth, and whom it pleases Him that we should obey, now and henceforward, whether he who is called Martin, he who is called Clement, or he who is called Benedict; and in whom we are to believe, if secretly, or by any dissembling, or publicly; for we are all ready to do the will and pleasure of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Yours in all things,

Count d’Armagnac.[37]

That outlier third, Benedick XIV[38] was from a city within the Count's territory, so perhaps he was looking to put him down ("who dubs himself"). Or, he really wanted to know what the Maid thought on the matter. It's all very strange, as the Count wrote the letter from Sully in northeastern France, and he was opposed to Charles VII. Joan was inundated with these types of inquiries, by letter or in person.[39]

Joan dictated a reply to the Count's messenger, which is rather clever and to which her testimony at the trial corresponded:

Jhesus Maria. Count d’Armagnac, my very good and dear friend, I, Jeanne, the Maid, acquaint you that your message has come before me, which tells me that you have sent at once to know from me which of the three Popes, mentioned in your memorial, you should believe. This thing I cannot tell you truly at present, until I am at rest in Paris or elsewhere; for I am now too much hindered by affairs of war; but when you hear that I am in Paris, send a message to me and I will inform you in truth whom you should believe, and what I shall know by the counsel of my Righteous and Sovereign Lord, the King of all the World, and of what you should do to the extent of my power. I commend you to God. May God have you in His keeping! Written at Compiègne, August 22nd.

From the trial:

Court: "Is this really the reply that you made?”

Joan: “I deem that I might have made this answer in part, but not all.”[40]

Court: “Did you say that you might know, by the counsel of the King of Kings, what the Count should hold on this subject?”

Joan: “I know nothing about it.”

Court: “Had you any doubt about whom the Count should obey?”

Joan: “I did not know how to inform him on this question, as to whom he should obey, because the Count himself asked to know whom God wished him to obey. But for myself, I hold and believe that we should obey our Lord the Pope who is in Rome. I told the messenger of the Count some things which are not in this copy; and, if the messenger had not gone off immediately, he would have been thrown into the water—not by me, however. As to the Count’s enquiry, desiring to know whom God wished him to obey, I answered that I did not know; but I sent him messages on several things which have not been put in writing. As for me, I believe in our Lord the Pope who is at Rome.”

Must have terribly disappointed the old boys at Rouen and Paris, as a primary reason for their siding with the English and for so vigorously pursuing Joan, as Pernoud discusses, was to affirm their power over the Papacy as well as over the French King.

The Western Schism was settled by granting to the a General Council of bishops the power to remove a Pope from office, which was done with the acquiescence of the Roman Pope, who after removal of the two other competing Popes, himself resigned to be replaced by a Pope selected by the General Council, Martin V.[41] The exercise of power by the Council is known as "conciliarism," which may be seen as

Joan's voices didn't advise her on the issue of the papacy, so, as she said, she spoke for herself. Still, her impact on the issue was significant. A first question is if her reference to "the lord pope who is in Rome" is to Martin V or to Rome as the seat of the Papacy. It appears to be the latter, which would suggest something more than just Joan's "good sense," which the historian Michelet attributed to her authority rather than her voices. Rome had become unstable and subject to mob rule and invasion. It lay at the border of the Kingdom of Naples, which supported the Avignon papacy. Martin V's primary job was to secure and rebuild Rome itself. While subject to the General Council, by restoring the Vatican and the city around it, Martin V laid the foundation for the modern Papacy, which quickly overshadowed conciliarism, which was condemned at the Fifth Lateran Council (1512-1517).

>> here

Joan has no say in any of these affairs, but by coronating Charles VII at Rheims, she secured the necessary monarchical authority for secure Roman Catholic hold on France, be it Gallic in nature. For both Saints Catherine of Sienna and Joan of Arc, the papacy must be seated in Rome. Saint Catherine explicitly sought Christian unity, while Joan led a fight of Christian against Christian, but it was a fight Joan helped to end and not start, and she lamented the loss of life on both sides. A united France for Joan meant a united Church.

Historians correctly attribute the Western Schism to the origins of the Protestant Reformation itself. At the Council of Constance, which ended the schism, Proto-Protestant Catholic priest John Wycliff was posthumously condemned for heresy and his body ordered exhumed and burned, and his follower Jan Hus was defrocked and handed over to hostile secular authority which burned him at the stake. Both men challenged the authority of the Pope -- which brings up a larger question as to which Pope. Wycliff was active before the Western Schism, but wrote his most radical tracts after it. Wycliff would have come of age with fresh memories of previous Schism, as well as with the outbreak of the Hundred Years War. Hus, who received Holy Orders in 1400, was a clear product of the Schism, which had divided the University of Prague where he studied and became master, dean and rector in 1409. Hus' most drastic attacks on the abuses of the papacy were directed at the antipope John XIII who was using (abusing) the authority he (did not) had to collect tithes. In other words, both men were products of a fractured Church that Saints Catherine and Joan sought to repair.

>> Joan swears to Martin >> why ? Martin V, who ended the schism and who started the Univ. at Leuvain, was elected pope on St. Martin's Feast Day. Here for St. Martin: Martin of Tours - Wikipedia

> these two saints admonishsed church unity at Rome ... but the divisions had already set the larger problem that Joan had to save Franch from, Jan Hus ... or his suporters were at th Council of << that settled the 2nd avignon schism.

> Bridget predictd the reduced and exact size of the Vatican in 1922

>> note: the French king withdrew support of avignon in 1398 Antipope Benedict XIII - Wikipedia[42] He was run out of Avignon, but returned w/ great popular support and affirmed by France, Scotland, Castille and Sicily. 1408 Chas VI declared neutrality

< he started the Univ of Glasgw )?( ... then loast France adn had to run from Avignon by 1413 ... then Constance 1415 refused, ws excommnicated in 1417 when Martin came on, ran to Aragon (Tortosa)

>> CHas VII and Pragmatic Sanction << note that a false pragmatic sanction supposedly issued by Saint Louis was circulated when Chas VII was adopting his own. It was not real.

>> councils >> get on Pernoud's obsession w/ them and warning about Joan's opposition to them

> Henry IV > only protestant king of France.. renounced protestantism at St. Denis " "Paris is well worth a mass".

>> House of Valois ended w/ two last (?) kins protesters

Saint or Servant of France?

During and since Joan's time, French patriots have looked to Joan for glory of France. Until the French Revolution, however, she was a mark of glory for both the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. During the Revolution, the Jacobins suppressed any Catholic or monarchical associations, including her annual festival in Orléans that had centered around the Cathedral of Sainte-Croix, where Joan celebrated a Vespers Mass during the siege. Joan nevertheless remained useful for the Revolution as a symbol of the common people and "independence."[43]

Napoléon renewed the celebrations that the Jacobins had halted and also restored her birthplace at Domrémy as a national monument.[44] His embrace of Joan met several needs: French nationalism, especially anti-British French nationalism, reinforcement of the Concordat of 1801 between the French government and the Vatican that officially restored the Church in France, and legitimization of his own mission to glorify France and himself as her savior.

Further along, we see Joan's popularity arise during times of crisis or national pride, such as the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, both World Wars, and French post-War nationalism under Charles de Gaulle.[45] While modern academics have co-opted Joan for various agenda, from feminism and anti-patriarchy, to cross-dressing and "gender fluidity",[46] seeing in Joan everything but French nationalism and the Catholic faith, which, in turn, they deplore when Joan's image is adopted by "far right" monarchists[47] and nationalists. Nevertheless, while seemingly all things to all people, Joan remains a dominant symbol of France, and correctly so.

What goes missing is her Catholicity and sainthood. Despite depictions of her visions and divine associations such as that of a panel in La Vie de Jeanne d'Arc at the Panthéon in Paris of a Dove escaping Joan's mouth at her death, the secularization of Joan that started with Voltaire's crude and demeaning 1730s play about her continues. Voltaire ridiculed Jean Chapelain's 1656 epic poem about Joan that emphasized her divine mission, which, as one modern academic frames it, "is devoted entirely and equally to Church and monarchy." Oh, and the poem itself is "turgid."[48] Voltaire mockery not just Chapelain, but the Maiden herself, and, of course, her virginity:

That Joan of Arc had all a lion's rage ; You'll tremble at the feats whereof you hear, And more than all the wars she used to wage, At how she kept her maidenhead — a year ![49]

He goes on to compare Joan to the Medusa and has her riding into battle naked. But no need to get into it any further here, as Voltaire's tantrum was more about his own anti-Catholic bigotry than Joan of Arc. She was merely a useful target.

On it goes through the progression of modernity, exemplified by the 1844 work of Jules Michelet, a 19th century anti-clerical French historian. Michelet is the originator of the term "Renaissance," meant to describe the end of an abysmal and backward Medieval period marked by superstition, oppression, and the Catholic Church (especially Jesuits), replaced by a "rebirth" of enlightened antiquity. Sadly, this socialist historian has deeply influenced the modern study of history.

The term "Dark Ages" was first used in the 1300s by Petrarch, the Catholic scholar and often deemed founder of humanism. Petrarch, who lived a century before St. Joan, described the conditions in Europe following the fall of the Roman empire up to his own day as "dark." Michelet applied Petrarch's "light" of antiquity to its supposed rebirth in the "light" of the Renaissance:

Nature, and natural science, kept in check by the spirit of Christianity, were about to have their revival, (renaissance.)[50]

All the while consigning to the dark Petrach, and thus, Dante and other early "Reniassance" figures for Michelet, there was one "dark ages" ambassador to hold on to: Joan of Arc, whom he called "The Maid of Orleans."[51] For Michelet, Joan was a "simple Christian," that is a good Christian as opposed to the clerics around her, bad Christians all. While considering her visions mundane and common,[52], he presents her divinely-directed acts as if they just, well, happened.[53] Here the historian's judgment is blinded by his prejudice, and like every secular take on her that dismisses the divine hand:

The originality of the Pucelle, the secret of her success, was not her courage or her visions, but her good sense.[54]

Beyond that any application of "good sense" would have bound Joan to the fields of her home village, Domrémy, the only thing Michelet can do with her religiosity is to ignore it when inconvenient, exalt it when it contrasts with the hated clerics, and otherwise treat it metaphorically as just a backdrop to her true purpose, according to Michelet, ransoming France:

The Imitation of Jesus Christ, his Passion reproduced in the Pucelle -- such was the redemption of France.[55]

I can't even begin to process the association of "redemption of France" with the "imitation" and Passion of Christ, and we're better off, as with Voltaire, just not going there. But Michelet gets even more grotesque with his impassioned, shall we say, 19th century romanticization of femininity represented by Joan:

Purity, sweetness, heroic goodness — that this supreme beauty of the soul should have centred in a daughter of France, may surprise foreigners who choose to judge of our nation by the levity of its manners alone ... old France was not styled without reason, the most Christian people. They were certainly the people of love and of grace ; and whether we understand this humanly or Christianly, in either sense it will ever hold good. The saviour of France could be no other than a woman. France herself was woman;[56]

When the religious is replaced by the secular, the secular fills the empty space. Thus the Lincoln Memorial is a "temple" and George Washington rises to the heavens in a an "apotheosis" in the dome of the U.S. Capitol. Here Michelet transposes Joan's religiosity for France's raison d'être, claiming for France a soul that he otherwise denies in Joan. Michelet, as least, recognized in Joan a good Christian, but like scholars who have followed sees her faith as an anachronism and her visions as irrelevant at best.

The historical problem of Saint Joan

The most prominent modern biographer of Saint Joan is Régine Pernoud (1909-1998), a medieval scholar who warns,

Among the events which he expounds are some for which no rational explanation is forthcoming, and the conscientious historian stops short at that point.[57]

So the "conscientious historian" must contain himself to "the facts" and stick to sorting them out for description while avoiding explanation. It's not only impossible, it's historiographically useless: I can describe the Neolithic Revolution all day long, but if I don't attributed it to a cause I have learned nothing. Same with any historical moment, from the Roman ascension to the last American election. What good is history if it just says and does not explain? (If so, the entire profession would be out of a job.) But for Joan, so it is. Because her motives, actions, and outcomes are so improbable, to attribute them to anything other than divine guidance makes no sense. But since divine guidance is "ahistorical," or merely an article of faith to her and to us, Joan's motives don't matter. So Pernoud dismisses them altogether, falling back upon,

The believer can no doubt be satisfied with Joan’s explanation; the unbeliever cannot.[58]

So what does the "unbeliever" do with the evidence? We know she had voices. She testified to them consistently and honestly. No reading of the extensive record shows in her any hint of guile or manipulation. Like the Apostle Nathanael, "There is no duplicity in [her]."[59] To say, then, that the "unbeliever cannot" accept Joan's own explanations is an easy out from what is plain to see.

Instead we hear that it was schizophrenia or moldy bread, which at least recognize that Joan heard voices -- actually Joan didn't just hear voices of Saints, she interacted with them, telling her interrogators of kissing the feet of Saints Catherine and Margaret. Pernoud, however, neither asserts nor denies Joan's voices, which is a complete copout.

Unlike the historian, the actors of Joan's day had to to decide: either Joan acted on voices of God -- or of Satan. There was no in between.

Imagine writing a book on the life of Jesus as a non-believer.[60] You would get caught up in denying the Lord's virgin birth, denying the miracles, denying the resurrection, and, ultimately, as some do, denying his historical presence altogether -- understandably so, as the story of Christ makes no sense without his divinity.[61] Accepting his historicity without the miraculous requires denying the authenticity of the Gospels and attributing them to post hoc contrivances.[62] It gets messy and, frankly, serves merely to deny Christ rather than understand him.

Similarly, once you see the divine hand in Saint Joan's story, it all makes sense, and you won't be able to conceive that what she did could have happened without God's hand. Deny the divinity and it makes no sense. And that's where Pernoud lands. She denies that Joan was, in CS Lewis' terms[63], a madman, but neither was she divinely guided. So all we have left is that she was a liar -- and thus of the devil, something Pernoud, a deep admirer of Joan, never broaches, although the English put her to death for it.

Lewis prefaces his argument by noting,

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say.

The logic applied to Joan goes the same way: treating her merely as an historical character debases what she was and did. So it is that Pernoud concludes that when "confronted by Joan" all we can do is to "admire" her, as the common people have since the 15th century, for "in admiring [they] have understood her":

They canonised Joan and made her their heroine, while Church and State were taking five hundred years to reach the same conclusion.[64]

That's as close as Pernoud will come to an historical "saint" Joan -- that she was "canonized" in the hearts of her countrymen. While affirming Joan's popular canonization (okay), Pernoud incorrectly claims that the "Church and State" didn't understand her until 1921, forgetting that Joan's "Rehabilitation Trial" and its declaration of her innocence was, in Pernoud's own words, "in the name of the Holy See."[65] Worse, this historian ought to know that very few of the laity were canonized before the 20th century, including the 16th century Saint Thomas More, who wasn't canonized until 1935, and with great hostility for it from the Anglican Church. Saint Joan's canonization underwent a similar dynamic, but was further delayed by the intervention of the French Revolution and subsequent 19th century European anti-clericalism and anti-monarchism. Free of having to address whether Joan's spiritual events were real or not, Pernoud's historiography leads her to this sentimentalized and historically insufficient view of Joan's contemporaries and her legacy. So we get these dumb, dull statements of Joan's legacy, such as at end of one of her books,

It remains true that, for us, Joan is above all the saint[66] of reconciliation—the one whom, whatever be our personal convictions, we admire and love because, over-riding all partisan points of view, each one of us can find in himself a reason to love her.[67]

That's no better than this, from the collective wisdom of contributors to "Joan of Arc"'s entry at Wikipedia,

Joan's image has been used by the entire spectrum of French politics, and she is an important reference in political dialogue about French identity and unity.[68]

It's just gross: Joan is in the eye of the beholder. Worse, my concern is that an historiography that frees itself of having to address whether Joan's spiritual events were real or not leads to a misreading of the facts. We cannot comprehend the motives and choices of Joan herself, much less those of her followers without it. Some girl showed up, led an army, got abandoned by her friends and killed by her enemies. Thanks a lot. No, Joan is only real if her visions were real. Just ask the English and Burgundians who knew full well what this young woman had done and why.[69] The rage of the ecclesiastical Court and its English backers that condemned her is in inverse proportion to the glory of Joan's visions and the reality Joan and her people understood them to be. To read the epithet the English placed upon a placard by the stake is to understand just how real her voices were:

Joan, self-styled the Maid, liar, pernicious, abuser of the people, soothsayer, superstitious, blasphemer of God; presumptuous, misbeliever in the faith of Jesus-Christ, boaster, idolater, cruel, dissolute, invoker of devils, apostate, schismatic and heretic.[70]

It ought not take much faith to see straight through to the Crucifixion of the Lord himself here and the fury of his executioners, which stand for us in the Gospels as more evidence of the Lord's divinity. Uninformed by faith, the condemnation is just hyperbolic political statement. Oh no, it wasn't. They meant it, and meant it hard. Listen to Jean Massieu, Joan's escort to and from the trial,

I heard it said by Jean Fleury, clerk and writer to the sheriff, that the executioner had reported to him that once the body was burned by the fire and reduced to ashes, her heart remained intact and full of blood, and he told him to gather up the ashes and all that remained of her and to throw them into the Seine, which he did.

Or Isambart de la Pierre, a Dominican priest who witnessed the trial,

Immediately after the execution, the executioner came to me and my companion Martin Ladvenu, struck and moved to a marvellous repentance and terrible contrition, all in despair, fearing never to obtain pardon and indulgence from God for what he had done to that saintly woman; and said and affirmed this executioner that despite the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal which he had applied against Joan’s entrails and heart, nevertheless he had not by any means been able to consume nor reduce to ashes the entrails nor the heart, at which was he as greatly astonished as by a manifest miracle.[71]

Now we're talking! So let's re-write this historian's own epithet for Joan, only with faith and love in Christ, as Joan's canonization is to be celebrated, not used as a weapon against Joan's own faith.

They believed in Joan and made her their heroine, affirmed by Mother Church with her official and glorious canonization on May 9, 1921 and followed by State declaring July 10, her Feast Day, a national holiday.

>>here After Joan's presentation to the Dauphin at Chinon, the Archbishop of Embrun, Jacques Gélu, warned the Dauphin to be careful with a peasant girl from a class that is "easily seduced." After Orleans, The Bishop had a change of heart. Applying the formula of the Evangelist, "by their fruits ye shall know them," he wrote,

We piously believe her to be the Angel of the armies of the Lord.[72]

He advised the Dauphin,

do every day some deed particularly agreeable to God and confer about it with the maid.[73]

- ↑ Henry IV, crowned in 1399, was the first English king of the Norman period to speak English natively. Passed under the French-speaking Henry III, the 1362 Statute of Pleading made English the official language. Since the English by then had lost most of their holdings in France, Henry III needed to embrace an English national identity.

- ↑ His predecessors were Kings of the Franks; Philip II was the first to declare himself King of France.

- ↑ He is supposed to have had iron rods sewn into his gown to keep himself sturdy and not break. His psychoses manifested in various other ways, including to forget who he was or those around him and to run around the palace hysterically. Up until the late Biden presidency, I might have used the situation as an example of the insanity of monarchy, as why'd they keep the crazy man in power? Well, as with the incompetent Joe Biden, those in power around him depended on the King's title for their own power. We will see how this dynamic impacts Saint Joan.

- ↑ In words she led him to the coronation

- ↑ Italy was subject to foreign rule, so it would have followed a French trajectory, and thus compromising Rome. Spain, however, may have stayed Catholic, although without a Catholic France it becomes doubtful.

- ↑ "Bastard" was a neutral description to indicate that his father wasn't married to his mother. The use of "Orlėans" in his name indicated high rank, as the Duke d'Orlėans was his half-brother. He was first cousin to the king, Charles VII. His actual name was Jean de Dunois. In 1439 he was made "Count of Dunois." The coolest title he held was Knight of the Order of the Porcupine.

- ↑ Charlemagne was canonized by the antipope Paschal III, whose acts were illegitimate, so Charlemagne is not recognized as a Saint. However, he has been venerated in France since Charles V (1338-1380), who led France to its highest points during the Hundred Years War, and so Joan would have considered him a Saint.

- ↑ which is why his reign is considered the precursor to the Holy Roman Empire

- ↑ filioque means "and the son" and is spoken in the Nicene Creed's "I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son" The filioque marks a theological division between the Eastern and Western Churches (which Charlemagne's coronation itself propelled, as his empire challenged Byzantine power). The filioque was traditionally used and was formally added to the Roman Rite in 1014.

- ↑ or Reims. I'm using "Rheims" because medieval French speakers liked their H's. I'm just speculating, but it's possible that the H in Rheims was aspirated, i.e. pronounced, so perhaps the dropped H marks a change in the pronunciation of the city's name. "Rheims" is the English (England) spelling, as seen by the "Douai-Rheims Bible." The French language Wikipedia entry on Reims (here) notes that "Rheims" is "orthographe ancienne".

- ↑ From CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Louis IX "St. Louis's relations with the Church of France and the papal Court have excited widely divergent interpretations and opinions. However, all historians agree that St. Louis and the successive popes united to protect the clergy of France from the encroachments or molestations of the barons and royal officers.

- ↑ It was Saint Louis who acquired the Crown of Thorns. He got it from the Emperor of Constantinople in exchange for paying off the emperor's tremendous debt of135,000 livres to a Venetian merchant. In an exemplary Christian act, Louis IX fined the Lord of Coucy 12,000 livers (a lot!) for hanging three poachers and had part of the money dedicated to Masses in perpetuity for the souls of the Count's three victims.

- ↑ A few years before, 1258, Louis settled a dispute with the King of Aragon by trading respective feudal lordship over regions in Spain and France. As to the treaty with the English, French historian Édouard Perroy argued that the vassal status of English lands negotiated in the Treaty of Paris was unsustainable and caused discontent and instability that led to the Hundred Years War. Maybe. Here from the CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Louis IX "It was generally considered and Joinville voiced the opinion of the people, that St. Louis made too many territorial concessions to Henry III; and many historians held that if, on the contrary, St. Louis had carried the war against Henry III further, the Hundred Years War would have been averted. But St. Louis considered that by making the Duchy of Guyenne a fief of the Crown of France he was gaining a moral advantage; and it is an undoubted fact that the Treaty of Paris, was as displeasing to the English as it was to the French."

- ↑ or Charles V who recovered much of France in the second phase of the Hundred Years War in the 1370s.

- ↑ There were six, actually.

- ↑ The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, or Barbarossa (reigned 1155-1190), orchestrated the canonization of Charlemagne at Aachen in Germany under the antipope Paschal III. Holy Roman Emperors had a bit of a habit of appointing antipopes (popes in their eyes), which asserted their power and that of their supporting bishops. With his long reign, Barbarossa backed four antipopes to oppose Pope Alexander III (1159-1181), but he was unable to outmaneuver Alexander, who gained the upper hand when kings of England, France and Hungry backed him, largely by way of contesting Holy Roman Empire's hold on Italy. (Alexander III spent most of his papacy outside of Rome.) Barbarossa capitulated after his forces were defeated by the Lombard League, which supported Alexander, at the Battle of Legnano in northern Italy in 1176. Alexander consolidated his papal rule at the Third Council of Lateran in 1179, which formally brought an end to the schisms.

- ↑ Pope Alexander III nullified the acts of Barbarossa's antipopes, including that of Paschall III to canonize Charlemagne. Alexander also forced the English Henry II into a year of penitence for the murder of Samuel Becket, who was canonized by Alexander shortly after his death in 1170.

- ↑ The Eastern Schism would be the earlier break with the Easter church at Byzantium.

- ↑ The Schism was ended by the Council of Constance (1414–1418) that was made possible by the 1415 resignation of the Roman Pope Gregory XII. The Council deposed the sitting Avignon (anti)Pope, Benedict XIII, and another (anti)Pope at Rome, John XXIII, and then elected in 1417 Martin V. Originally backed by certain French bishops and various regions in Italy and Germany, John XXIII left Rome but ended up surrendering and being tried for heresy. The Avignon (anti)Pope Benedict XIII fled to the protection of the King of Aragon, continuing his claim as Pope of Avignon. His successor under the Aragon King was Clement VIII (1423-1429) although a dissenting Cardinal (of four who selected Clement) from Rodiz, France, in 1424 made a one-man appointment of his sacristan as (anti)Pope Benedict XIV.

- ↑ The Aragon King Alfonso V did not have the support of the Aragon bishop in his backing of Clement VIII, but he did so in his pursuit of Naples. When antipope Clement VIII abdicated, he and his supporting Bishops held a proforma election for Martin V (who was already Pope), thus affirming their loyalty, as well as to perform a penitential in forma submission to Martin.

- ↑ When the expedition's military commander, Sciarra Colonna, demanded the Pope's abdication and was told that the Pope would "sooner die," Colonna slapped him. The incident is known as the schiaffo di Anagni ("Anagni slap"). Boniface had been caught up in a feud within the Colonna family which led to devastation of villages by one brother over the assurances from Boniface that they would be spared. Dante Alighieri avenged the incident by placing Boniface in the Eight Circle of Hell in The Inferno.

- ↑ Benedict XI, as Cardinal Niccolò of Treviso, was present at the attack on Boniface at Agnini.

- ↑ Benedict XI was known for his holiness, and over the years his tomb came to be associated with numerous miracles. In 1736 he was beatified, so he is "Pope Blessed Benedict XI."

- ↑ The Roman mobs disliked having a Neapolitan pope only slightly less than they disliked having a French pope.

- ↑ Urban IV was stepping on lots of toes as he tried to reel back clerical political entanglements. For the Count of Agnagi, see Onorato Caetani (died 1400) - Wikipedia

- ↑ His uncle, the Bishop of Rouen, was the Avignon Pope Clement VI. Beaufort was a "Cardinal Deacon" and not a priest, and hesitated to accept the position. (See The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church - Conclaves by century) He was ordained the day before crowning as Gregory XI. For his biography, see CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Pope Gregory XI

- ↑ See Pope Urban V - Wikipedia

- ↑ Wycliffe's radicalism led to Gregory's five 1377 Bulls against Wycliff.

- ↑ From Urban V's return to Rome through to her death, Bridget remained in Rome but focused setting up and financing her order and on other spiritual matters.

- ↑ Saint Catherine of Siena, 1347-1380 | Loyola Press

- ↑ Saint Joan of Arc issued similar exhortations. In what seems a reference to Catherine of Sienna, although she was not yet canonized, an English witness of Joan at the trial compared her to Catherine: "Her incontestable victory in the argument with the masters of theology makes her like another Saint Catherine come down to earth." Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 131). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ How St. Catherine Brought the Pope Back to Rome | Catholic Answers Magazine cites St. Catherine of Siena as Seen in Her Letters, ed. Vida D. Scudder (London, 1911), 165-166. The webpage seems to conflate this letter with another from that source on p. 185. << to cofirrm

- ↑ As did the 19th century French historian Michelet, it's easy to forget that this is at the cusp of what Michelet termed the "Renaissance," which means this period and the "Renaissance" were actually one, not distinct periods. A lot was going on.

- ↑ Catherine became famous across Tuscany as a holy woman (santa donna) for her acts of charity, especially for the sick, as well as her calls for clerical reform general repentance through "total love for God." Florence was in rebellion from the Papal States and under a papal interdict, so it was thought that Catherine, who called for reconciliation with the Vatican, could yield advantageous returns. However, both sides succumbed to distrustful elements who did not want to see her succeed. After Gregory XI moved to Rome, he sent her back to Florence, this time on his behalf. While she was there, Gregory died and street riots broke out, likely due to longstanding frustration with the papal interdict, the larger conflict which had disrupted the economy and led to increased taxes, and the general policies of the guilds that ran Florence. That July a more general rebellion arose, the Ciompi Revolt, led by discontented wool workers in which Saint Catherine was nearly killed. The shocked calm that followed the rebellion led to reconciliation with the new Pope Urban VI.

- ↑ How St. Catherine Brought the Pope Back to Rome | Catholic Answers Magazine

- ↑ Typo or mistake: it was Clement VIII

- ↑ Jeanne D‘arc, by T. Douglas Murray (Gutenberg). Murray uses a different translation from Pernoud.

- ↑ There were two Benedict XIVs, the first supported by a Cardinal from Rodiz in southern France named Jean Carrier. When the first XIV died, Carrier appointed himself Pope Benedict XIV. Carrier was later captured by the other antipope Clement VIII and imprisoned until he died.

- ↑ See examples in Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 127). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ That indicates either that the letter was not entirely of her words, or what was presented to the court was incomplete. Likely the latter.

- ↑ Charles VI had earlier declared himself neutral between the the Avignon and Roman Popes, which left the last Avignon Pope, Benedict XIII without sufficient support. Nevertheless, he refused to concede and was excommunicated by the General Council.

- ↑ In 1398, the Kingdom of France withdrew its recognition of the Avignon anti-popes. Benedict was abandoned by 17 of his cardinals, with only five remaining faithful to him.

- ↑ There is much irony in the Revolution's relationship to Saint Joan. It's like Christmas: a great holiday, but all that religious stuff keeps getting in the way. Here for a short essay on the hostility of the Jacobins towards the Church: The Dechristianization of France during the French Revolution - The Institute of World Politics

- ↑ For use of Joan's image before and after the French Revolution, see SEXSMITH, DENNIS. “The Radicalization of Joan of Arc Before and After the French Revolution.” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 17, no. 2 (1990): 125–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42630458.

- ↑ Even the Vichy government, used Joan for anti-British propaganda (see "Joan of Arc: Her Story", from the Preface by the translator, Jeremy Duquesnay Adams, p. XIX)

- ↑ Of all the claims upon Joan, one of the most ludicrously absorbed in a fleeting historical moment, this from the 1980s, is that "Joan's mission now seems ... something of a model for modern movements of popular resistance to anti-colonialism" (Pernoud, p. 4)

- ↑ Who knew! Seems that the 3,000 members of the Action Française, a remnant of a late 19th, early 20th century nationalist movement still has them scared and appalled at their use of Joan of Arc's memory. On the Wikipedia page for the Action Française - Wikipedia is a 1909 photo of a Action Française youth group being arrested on the Fête de Jeanne d'Arc (the caption incorrectly calls it the "Feast Day of Joan of Arc," as she was not canonized for another eleven years.

- ↑ SEXSMITH, DENNIS. “The Radicalization of Joan of Arc Before and After the French Revolution.” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 17, no. 2 (1990): 125–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42630458.

- ↑ La Pucelle, the maid of Orleans: : Voltaire, 1694-1778 (archive.org) It's always useful to recall that on his deathbed Voltaire begged the Lord for forgiveness, and when rewarded with extra time upon his recovery, he squandered it and ultimately renounced God on his final death.

- ↑ History of France : Michelet, Jules, 1798-1874 (archive.org), p. 17

- ↑ A major section of Michelet's "History of France" was dedicated to "The Maid of Orléans"

- ↑ "Who but had visions in the middle age?"; p. 131

- ↑ For example, Michelet flatly reports Joan's recognition of the Dauphin upon her entrance to the Court at Chinon, as well as to call it a "very probable account" her private conversation with the Dauphin in which she repeated to him a prayer he had made in private (p. 136 and footnote ||).

- ↑ p. 131

- ↑ p. 124

- ↑ p. 169. We might get into Michelet's obsession with female archetypes, which were part of his historical theories, but we'll just leave it at this.

- ↑ Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 387). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 388). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Jn 1:47

- ↑ Actually, just go to the Wikipedia entry "Jesus" and there you have it.

- ↑ Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim tried to do it with "Jesus Christ Superstar," but all they did was to fashion a story that turned Judas into a hero.

- ↑ Constantine's vision that led him to put the ChiRho on the shields of his soldiers is said to be an after-the -fact construct from a vision he told about later in his life. On the surface, it doesn't matter: he won the battle at the bridge. But then we're left with an entirely inexplicable conversion There is a stronger case to be made for that exact circumstance with the life of Mohammed and creation of Islam as a post hoc justification for Arab conquest through co-option of the Abrahamic religions.

- ↑ Lewis's formula, called a "trilemma," is most directly stated by him as, " Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse" (Mere Christianity, p 52 in my copy; it's at the end of Ch.3.), that is, he is either a lunatic, a liar, or God.

- ↑ Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 391). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 379). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ note the lower case "saint"

- ↑ Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 391). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Joan of Arc#Legacy - Wikipedia

- ↑ See John, Duke of Bedford, his feelings are known to us from a letter which he wrote in 1434, summing up events in France for his nephew the King of England: “And alle thing there prospered for you, til thety me of the siege of Orleans taken in hand, God knoweth by what advis. At the whiche tyme, after the adventure fallen to the persone of my cousin of Salysbury, whom God assoille, there felle, by the hand of God, as it seemeth, a greet strook upon your peuple that was assembled there in grete nombre, caused in grete partie, as y trowe, of lakke of sadde beleve, and of unlevefulle doubte that thei hadde of a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle, that used fais enchauntements and sorcerie. The which strooke and discomfiture nought oonly lessed in grete partie the nombre of youre people, there, but as well withdrowe the courage of the remenant in merveillous wyse, and couraiged youre adverse partie and ennemys to assemble hem forthwith in grete nombre.” Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 128). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ From the entry of an English recorder of the events on behalf of Parliament. On the "mitre" put on her head was, "heretic, relapsed, apostate, idolater" (as quoted in Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (p. 340). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition).

- ↑ Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses (pp. 332-333). Scarborough House. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ The maid of France; being the story of the life and death of Jeanne d'Arc : Lang, Andrew, 1844-1912 (archive.org)

- ↑ Pernoud, Joan of Arc: her story; p. 184