Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431) called herself, Jeanne la Pucelle,[1] meaning "Joan the Maid." Such was her name to others, followers or enemies, who also called her, simply, La Pucelle (the Maid). And so her main accuser spitefully call her "Joan, whom they call the Maid,"[2]

Jeanne, or Jehanne, is feminine for John, which means "God favors," and which is echoed by the name given her in the sole literary work composed during her time, the Pucelle de Dieu ("Maid of God").[3]

It was not until after her martyrdom that she was called "Joan of Orleans" or "the Maid of Orleans" in reference to her miraculous intervention in the Hundred Years War, the final turning point of which was the relief of the city of Orléans from an English siege, conducted under Joan's improbable and brilliant military command. The historical record shows that it was at her "Trial of Rehabilitation," starting 1452, that she was first referred to as "Joan of Arc".[4]

Joan of Arc saved France, and doing so saved Catholicism itself, which may well have been her mission all along. She was canonized by the Catholic Church in 1920.

This page presents a Catholic view of Saint Joan that is consistent with the history. It reviews the facts of the life and accomplishments of Saint Joan of Arc, as well as their historical context. It offers commentary and criticism of historical and academic views of Joan, especially as regards the secularization and ideological contortions of her legacy. Presented here, as well, is the theory that Joan's mission was not to save France so much as to save Roman Catholicism.

And, this page assumes everything that Joan testified to was real, not just to her, but objectively real to all.

** page under construction **

Related pages:

- Joan of Arc Timeline

- Kings of France and England

- Popes and antipopes

- Saint Joan of Arc Glossary for names, places & terms, as well as a flow chart of the lineage of French Kings (which can otherwise be confusing)

Here for Saint Joan of Arc category list of related pages

Joan for real?

Joan's biographers like to introduce Joan with a letter she composed to the King of England the day she was given authority over the French army. It's a marvelous, crazy letter, almost arrogant at first glance. A second look, though, and the letter yields instead Joan's simplicity and directness. Indeed, she is hardly arrogant: just brutally honest:

“Jhesus †Maria. “King of England; and you, Duke of Bedford, who call yourself Regent of the Kingdom of France; you, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk; John, Lord Talbot; and you, Thomas, Lord Scales, who call yourselves Lieutenants to the said Duke of Bedford: give satisfaction to the King of Heaven: give up to the Maid[5], who is sent hither by God, the King of Heaven, the keys of all the good towns in France which you have taken and broken into. She is come here by the order of God to reclaim the Blood Royal. She is quite ready to make peace, if you are willing to give her satisfaction, by giving and paying back to France what you have taken.

It's a useful letter for the biographer, because it launches her story perfectly. But left unexplained or unattributed to anything but "voices", as they tend, rather agnostically, it makes no sense: okay, so this illiterate girl from a little village hears voices that tell her she will save France and crown the King. She insists on an introduction to that prince, gets the interview, somehow picking him out of a crowd, undergoes three weeks of questions by all the king's finest minds, and passing the test is given a suit of armor and command of the French army. Okay...got it. Thank you, historians. But really?

Let's try it this way: Four years before, God sends Saint Michael the Archangel and Saints Margaret and Catherine to visit with a young girl in a small town in eastern France. Her country is at war and civil war, the Church is in a state of disruption, with an ongoing antipope claim, proto-protestant rumblings, and the "conciliarism" movement against papal authority gaining strength as a result of a series of papal schisms. Over time, the Archangel and the Saints prepare the young girl spiritually for her mission. In 1428, as the city of Orleans is subjected to a siege by English forces, they now tell her what she will do: save the city and crown the king -- in a city held by the enemy.

Now we can better understand her letter, which went on to explain that the English would do better to abandon Orléans and France itself. She concluded with the warning to the English commander,

You, Duke of Bedford, the Maid prays and enjoins you, that you do not come to grievous hurt. If you will give her satisfactory pledges, you may yet join with her, so that the French may do the fairest deed that has ever yet been done for Christendom. And answer, if you wish to make peace in the City of Orleans; if this be not done, you may be shortly reminded of it, to your very great hurt. Written this Tuesday in Holy Week, March 22nd, 1428.

Later, held captive and subjected to a trial known as the Trial of Condemnation, this letter was presented as evidence against her. After it was read out load, Joan corrected a couple lines, then proclaimed,

Before seven years are passed, the English will lose a greater wager than they have already done at Orlėans; they will lose everything in France. The English will have in France a greater loss than they have ever had, and that by a great victory which God will send to the French.

How do you know this?

I know it well by revelation, which has been made to me, and that this will happen within seven years; and I am sore vexed that it is deferred so long. I know it by revelation, as clearly as I know that you are before me at this moment.

When will this happen?

I know neither the day nor the hour.

In what year will it happen?

You will not have any more. Nevertheless, I heartily wish it might be before Saint John’s Day.[6]

She made the prediction on March 1, 1431. Six years and six months later, in September of 1437, Paris was delivered to the French through the Treaty of Arras, which ended the English alliance with the Duke of Burgundy and from which, in the Hundred Years War, the English would never recover.

Saint or Servant of France?

During and since Joan's time, French patriots have looked to Joan for glory of France. Until the French Revolution, however, she was a mark of glory for both the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. During the Revolution, the Jacobins suppressed any Catholic or monarchical associations, including her annual festival in Orléans that had centered around the Cathedral of Sainte-Croix, where Joan celebrated a Vespers Mass during the siege. Joan nevertheless remained useful for the Revolution as a symbol of the common people and "independence."[7]

Napoléon renewed the celebrations that the Jacobins had halted and also restored her birthplace at Domrémy as a national monument.[8] His embrace of Joan met several needs: French nationalism, especially anti-British French nationalism, reinforcement of the Concordat of 1801 between the French government and the Vatican that officially restored the Church in France, and legitimization of his own mission to glorify France and himself as her savior.

Further along, we see Joan's popularity arise during times of crisis or national pride, such as the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, both World Wars, and French post-War nationalism under Charles de Gaulle.[9] While modern academics have co-opted Joan for various agenda, from feminism and anti-patriarchy, to cross-dressing and "gender fluidity",[10] seeing in Joan everything but French nationalism and the Catholic faith, which, in turn, they deplore when Joan's image is adopted by "far right" monarchists[11] and nationalists. Nevertheless, while seemingly all things to all people, Joan remains a dominant symbol of France, and correctly so.

What goes missing is her Catholicity and sainthood. Despite depictions of her visions and divine associations such as that of a panel in La Vie de Jeanne d'Arc at the Panthéon in Paris of a Dove escaping Joan's mouth at her death, the secularization of Joan that started with Voltaire's crude and demeaning 1730s play about her continues. Voltaire ridiculed Jean Chapelain's 1656 epic poem about Joan that emphasized her divine mission, which, as one modern academic frames it, "is devoted entirely and equally to Church and monarchy." Oh, and the poem itself is "turgid."[12] Voltaire mockery not just Chapelain, but the Maiden herself, and, of course, her virginity:

That Joan of Arc had all a lion's rage ; You'll tremble at the feats whereof you hear, And more than all the wars she used to wage, At how she kept her maidenhead — a year ![13]

He goes on to compare Joan to the Medusa and has her riding into battle naked. But no need to get into it any further here, as Voltaire's tantrum was more about his own anti-Catholic bigotry than Joan of Arc. She was merely a useful target.

On it goes through the progression of modernity, exemplified by the 1844 work of Jules Michelet, a 19th century anti-clerical French historian. Michelet is the originator of the term "Renaissance," meant to describe the end of an abysmal and backward Medieval period marked by superstition, oppression, and the Catholic Church (especially Jesuits), replaced by a "rebirth" of enlightened antiquity. Sadly, this socialist historian has deeply influenced the modern study of history.

The term "Dark Ages" was first used in the 1300s by Petrarch, the Catholic scholar and often deemed founder of humanism. Petrarch, who lived a century before St. Joan, described the conditions in Europe following the fall of the Roman empire up to his own day as "dark." Michelet applied Petrarch's "light" of antiquity to its supposed rebirth in the "light" of the Renaissance:

Nature, and natural science, kept in check by the spirit of Christianity, were about to have their revival, (renaissance.)[14]

All the while consigning to the dark Petrach, and thus, Dante and other early "Reniassance" figures for Michelet, there was one "dark ages" ambassador to hold on to: Joan of Arc, whom he called "The Maid of Orleans."[15] For Michelet, Joan was a "simple Christian," that is a good Christian as opposed to the clerics around her, bad Christians all. While considering her visions mundane and common,[16], he presents her divinely-directed acts as if they just, well, happened.[17] Here the historian's judgment is blinded by his prejudice, and like every secular take on her that dismisses the divine hand:

The originality of the Pucelle, the secret of her success, was not her courage or her visions, but her good sense.[18]

Beyond that any application of "good sense" would have bound Joan to the fields of her home village, Domrémy, the only thing Michelet can do with her religiosity is to ignore it when inconvenient, exalt it when it contrasts with the hated clerics, and otherwise treat it metaphorically as just a backdrop to her true purpose, according to Michelet, ransoming France:

The Imitation of Jesus Christ, his Passion reproduced in the Pucelle -- such was the redemption of France.[19]

I can't even begin to process the association of "redemption of France" with the "imitation" and Passion of Christ, and we're better off, as with Voltaire, just not going there. But Michelet gets even more grotesque with his impassioned, shall we say, 19th century romanticization of femininity represented by Joan:

Purity, sweetness, heroic goodness — that this supreme beauty of the soul should have centred in a daughter of France, may surprise foreigners who choose to judge of our nation by the levity of its manners alone ... old France was not styled without reason, the most Christian people. They were certainly the people of love and of grace ; and whether we understand this humanly or Christianly, in either sense it will ever hold good. The saviour of France could be no other than a woman. France herself was woman;[20]

When the religious is replaced by the secular, the secular fills the empty space. Thus the Lincoln Memorial is a "temple" and George Washington rises to the heavens in a an "apotheosis" in the dome of the U.S. Capitol. Here Michelet transposes Joan's religiosity for France's raison d'être, claiming for France a soul that he otherwise denies in Joan. Michelet, as least, recognized in Joan a good Christian, but like scholars who have followed sees her faith as an anachronism and her visions as irrelevant at best.

The historical problem of Saint Joan

The most prominent modern biographer of Saint Joan is Régine Pernoud (1909-1998), a medieval scholar who warns,

Among the events which he expounds are some for which no rational explanation is forthcoming, and the conscientious historian stops short at that point.[21]

So the "conscientious historian" must contain himself to "the facts" and stick to sorting them out for description while avoiding explanation. It's not only impossible, it's historiographically useless: I can describe the Neolithic Revolution all day long, but if I don't attributed it to a cause I have learned nothing. Same with any historical moment, from the Roman ascension to the last American election. What good is history if it just says and does not explain? (If so, the entire profession would be out of a job.) But for Joan, so it is. Because her motives, actions, and outcomes are so improbable, to attribute them to anything other than divine guidance makes no sense. But since divine guidance is "ahistorical," or merely an article of faith to her and to us, Joan's motives don't matter. So Pernoud dismisses them altogether, falling back upon,

The believer can no doubt be satisfied with Joan’s explanation; the unbeliever cannot.[22]

So what does the "unbeliever" do with the evidence? We know she had voices. She testified to them consistently and honestly. No reading of the extensive record shows in her any hint of guile or manipulation. Like the Apostle Nathanael, "There is no duplicity in [her]."[23] To say, then, that the "unbeliever cannot" accept Joan's own explanations is an easy out from what is plain to see.

Instead we hear that it was schizophrenia or moldy bread, which at least recognize that Joan heard voices -- actually Joan didn't just hear voices of Saints, she interacted with them, telling her interrogators of kissing the feet of Saints Catherine and Margaret. Pernoud, however, neither asserts nor denies Joan's voices, which is a complete copout.

Unlike the historian, the actors of Joan's day had to to decide: either Joan acted on voices of God -- or of Satan. There was no in between.

Imagine writing a book on the life of Jesus as a non-believer.[24] You would get caught up in denying the Lord's virgin birth, denying the miracles, denying the resurrection, and, ultimately, as some do, denying his historical presence altogether -- understandably so, as the story of Christ makes no sense without his divinity.[25] Accepting his historicity without the miraculous requires denying the authenticity of the Gospels and attributing them to post hoc contrivances.[26] It gets messy and, frankly, serves merely to deny Christ rather than understand him.

Similarly, once you see the divine hand in Saint Joan's story, it all makes sense, and you won't be able to conceive that what she did could have happened without God's hand. Deny the divinity and it makes no sense. And that's where Pernoud lands. She denies that Joan was, in CS Lewis' terms[27], a madman, but neither was she divinely guided. So all we have left is that she was a liar -- and thus of the devil, something Pernoud, a deep admirer of Joan, never broaches, although the English put her to death for it.

Lewis prefaces his argument by noting,

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say.

The logic applied to Joan goes the same way: treating her merely as an historical character debases what she was and did. So it is that Pernoud concludes that when "confronted by Joan" all we can do is to "admire" her, as the common people have since the 15th century, for "in admiring [they] have understood her":

They canonised Joan and made her their heroine, while Church and State were taking five hundred years to reach the same conclusion.[28]

That's as close as Pernoud will come to an historical "saint" Joan -- that she was "canonized" in the hearts of her countrymen. While affirming Joan's popular canonization (okay), Pernoud incorrectly claims that the "Church and State" didn't understand her until 1921, forgetting that Joan's "Rehabilitation Trial" and its declaration of her innocence was, in Pernoud's own words, "in the name of the Holy See."[29] Worse, this historian ought to know that very few of the laity were canonized before the 20th century, including the 16th century Saint Thomas More, who wasn't canonized until 1935, and with great hostility for it from the Anglican Church. Saint Joan's canonization underwent a similar dynamic, but was further delayed by the intervention of the French Revolution and subsequent 19th century European anti-clericalism and anti-monarchism. Free of having to address whether Joan's spiritual events were real or not, Pernoud's historiography leads her to this sentimentalized and historically insufficient view of Joan's contemporaries and her legacy. So we get these dumb, dull statements of Joan's legacy, such as at end of one of her books,

It remains true that, for us, Joan is above all the saint[30] of reconciliation—the one whom, whatever be our personal convictions, we admire and love because, over-riding all partisan points of view, each one of us can find in himself a reason to love her.[31]

That's no better than this, from the collective wisdom of contributors to "Joan of Arc"'s entry at Wikipedia,

Joan's image has been used by the entire spectrum of French politics, and she is an important reference in political dialogue about French identity and unity.[32]

It's just gross: Joan is in the eye of the beholder. Worse, my concern is that an historiography that frees itself of having to address whether Joan's spiritual events were real or not leads to a misreading of the facts. We cannot comprehend the motives and choices of Joan herself, much less those of her followers without it. Some girl showed up, led an army, got abandoned by her friends and killed by her enemies. Thanks a lot. No, Joan is only real if her visions were real. Just ask the English and Burgundians who knew full well what this young woman had done and why.[33] The rage of the ecclesiastical Court and its English backers that condemned her is in inverse proportion to the glory of Joan's visions and the reality Joan and her people understood them to be. To read the epithet the English placed upon a placard by the stake is to understand just how real her voices were:

Joan, self-styled the Maid, liar, pernicious, abuser of the people, soothsayer, superstitious, blasphemer of God; presumptuous, misbeliever in the faith of Jesus-Christ, boaster, idolater, cruel, dissolute, invoker of devils, apostate, schismatic and heretic.[34]

It ought not take much faith to see straight through to the Crucifixion of the Lord himself here and the fury of his executioners, which stand for us in the Gospels as more evidence of the Lord's divinity. Uninformed by faith, the condemnation is just hyperbolic political statement. Oh no, it wasn't. They meant it, and meant it hard. Listen to Jean Massieu, Joan's escort to and from the trial,

I heard it said by Jean Fleury, clerk and writer to the sheriff, that the executioner had reported to him that once the body was burned by the fire and reduced to ashes, her heart remained intact and full of blood, and he told him to gather up the ashes and all that remained of her and to throw them into the Seine, which he did.

Or Isambart de la Pierre, a Dominican priest who witnessed the trial,

Immediately after the execution, the executioner came to me and my companion Martin Ladvenu, struck and moved to a marvellous repentance and terrible contrition, all in despair, fearing never to obtain pardon and indulgence from God for what he had done to that saintly woman; and said and affirmed this executioner that despite the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal which he had applied against Joan’s entrails and heart, nevertheless he had not by any means been able to consume nor reduce to ashes the entrails nor the heart, at which was he as greatly astonished as by a manifest miracle.[35]

Now we're talking! So let's re-write this historian's own epithet for Joan, only with faith and love in Christ, as Joan's canonization is to be celebrated, not used as a weapon against Joan's own faith.

They believed in Joan and made her their heroine, affirmed by Mother Church with her official and glorious canonization on May 9, 1921 and followed by State declaring July 10, her Feast Day, a national holiday.

>>here After Joan's presentation to the Dauphin at Chinon, the Archbishop of Embrun, Jacques Gélu, warned the Dauphin to be careful with a peasant girl from a class that is "easily seduced." After Orleans, The Bishop had a change of heart. Applying the formula of the Evangelist, "by their fruits ye shall know them," he wrote,

We piously believe her to be the Angel of the armies of the Lord.[36]

He advised the Dauphin,

do every day some deed particularly agreeable to God and confer about it with the maid.[37]

Saving Catholicism

Saint Joan saved France, yes. But she more importantly saved Catholic France and thereby Catholicism itself, as had France fallen to what was to become English Anglican and Protestant rule, so likely would have fallen the rest of Catholic western Europe.[38]

When, just before the Battle of Orléans, Joan warned her lieutenant La Hire to quit futzing around and get busy so she could save France, she told him that it wasn't about her, it was about God:

This help comes not for love of me but from God Himself, who at the prayer of St. Louis and of St. Charlemagne has had pity on the city of Orléans.

Saints Louis and Charlemagne?[39]

Intercession of Saints Charlemagne & Louis

When Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Imperator Romanorum (emperor of the Romans) in 800, he crowned the Frankish king Charles (Carolus, Karlus) king of western Christianity, creating what would later become the Holy Roman Empire. In submitting as vassal to the Pope, Charlemagne legitimized both his own rule and that of Roman Catholicism across his empire.[40] Among the religious legacies of Charlemagne was the practice of the laity of memorizing and reciting the Our Father prayer and the Apostle's Creed with the filioque[41] and the traditional singing of "Noel" at coronations in honor of Charlemagne's coronation by the Pope on Christmas Day.

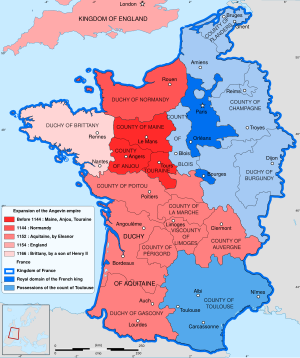

Saint Louis was the French king Louis IX (reigned 1226-1270). Crowned at Rheims,[42] he ruled as a devout and pious Christian to such extent that he was canonized not long after his death. Louis' reign was marked by consistent protection of the clergy and Church from secular rule and strict allegiance to the papacy.[43] He is considered the quintessential "Christian" -- but more correctly, Catholic, king.[44] As for historical context regarding Joan, in 1259 he consolidated French rule over Normandy at the Treaty of Paris with English King Henry III. Some historians attribute Louis' concession of Duchy of Guyenne to the English under French vassalage to the outbreak of the Hundred Years War, but there is no direct causality to make that connection, and even if there was any unfinished business Louis preferred settlement over continued war.[45]

If Joan's mission was to save France, Philip II (reigned 1165-1223) would have been the better intercessor, not Charlemagne or his grandson St. Louis, for Charlemagne's empire extended across Germany, and while Saint Louis extended French sovereignty, it was Philip who created the modern France that Joan defended.[46] Philip, in fact was the first to declare himself "King of France." Now, Philip was no Saint, as they say, so in Saints Charlemagne and Louis IX, perhaps Joan was appealing more to the Roman Catholic France than to the territorial one. Or, in that Joan's exhortation to La Hire was about Orléans and not France, perhaps "the prayer of St. Louis and of St. Charlemagne" was just for the city. But Orléans was the key to it all, as so went Orléans, so went France -- and, ultimately, French Catholicism.

The French King Charles V (reigned 1364-1380), who considered himself the fifth "Charles" of France,[47] promoted veneration of Charlemagne, including to dedicate a chapel to him at St. Denis with an elaborate reliquary, which treated him like a saint. The city of Rheims maintained a cult of Charlemagne and actively supported his canonization by the antipope Paschall III in 1165.[48]

>> fix < here? >> After resolving the 12th century schism of antipopes aligned with the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I ("Barbarossa"), Pope Alexander III annulled their papal acts, which included the canonization of Charlemagne.[49]

We can't say that it was of regional tradition or a remnant of the revoked canonization that Joan invoked, but we do know that when referring to "Saint Charlemagne" prior to Orléans, Joan was under the guidance of her voices. She invoked their names for a reason.

The Babylonian Captivity

Joan herself was born amidst an ongoing papal schism. When she was five years old, the "Western Schism"[50] of 1378 was finally settled with a consensus selection at Rome of Pope Martin V, although two rival claims persisted.[51] However, the antipope from Avignon, Benedict XIII, refused to concede, and he moved to Spain under the protection of the King of Aragon who used his presence there for leverage on other issues with Rome. It was Benedict's successor, the antipope Clement VIII who twelve years later finally gave up on the project on July 26, 1429 when the King of Aragon withdrew his support for him.[52] Note the date: Joan's triumph at Orléans was in May and the coronation of Charles VII at Rheims occurred on July 17. There is an interesting parallel to Joan in the Schism itself, precipitated by Pope Gregory XI's move from Avignon to Rome in 1377, ending the uncontested "Avignon Papacy" but prompting the schismatic, French-backed papacy back at Avignon. Known as the "Babylonian Captivity," the official Avignon papacy lasted through seven Popes across sixty-seven years. We see in these events an inversion of antagonists from that of Joan's day: Where the English provoked God's wrath in the Hundred Year's War, the French caught themselves up in less-than-holy entanglements during the Avignon period, which ended only after the intervention of another female Saint, Catherine of Sienna.

In 1289, Pope Pope Nicholas IV allowed the French King Philip IV to collect a one-time Crusades tithe from certain territories under Rudolf of Habsburg (who was not happy about it) in order to pay down Philip's war debts. With the costs of ongoing wars with Aragon, England and Flanders, Philip was up to his ears in financial gamesmanship, including debasement of the currency, bans on export of bullion, and seizure of the assets of Lombard merchants. In 1296, he imposed a severe tax upon Church lands and clergy in France, which didn't go over well with Rome. Pope Boniface VIII responded with the first of three Papal Bulls aimed at Philip denying his right to tax the Church without papal permission and generally asserting papal over secular authority.

The Pope compromised by allowing such a tax for emergencies only, and Philip went ahead anyway with at least some. Things escalated from there, with Philip prosecuting clerical agents from Rome in royal courts and the Pope issuing a wonderfully named Bull, Ausculta Fili ("Listen, My Son"), which Philip not only ignored but had burned in public. Boniface called the French Bishops to Rome, the assembly of which Philip preempted by convening the first Estates General in France, a council with representatives from the nobility, clergy, and commons. Boniface issued another Bull asserting Papal authority and excommunicated anyone, ahem, who prevented clerics from traveling to Rome. Philip did the obvious thing and sent a small army of sixty troops to arrest the Pope and force his abdication. The soldiers stormed the papal estate at Agnini, south of Rome, and held him for three days until residents retaliated and rescued the Pope from the French.[53] Now Philip got an excommunication directed at him personally. Boniface, though, likely from injuries or trauma suffered from the attack, and possibly from poisoning by the French, died shortly after.

Philip's excursion to Agnini put pressure on the subsequent Papal conclave to avoid further antagonism with him. The next Pope, Benedict XI, rescinded the excommunication but not that of Philip's minister who led the attack on Boniface[54], thus leaving the conflict unsettled. Benedict, though, died within a year,[55] and after a year-long impasse between French and Italian Cardinals at the ensuing Conclave, Philip had his way with selection of the Frenchman, Raymond Bertrand de Got, as Pope Clement V. Clement basically did Philip's will, which included effective rescindment of Boniface's Bulls, a posthumous inquisition into Boniface in order to discredit him (which failed), sanction of Philip's arrest of the Knights Templar, and, most importantly, move of the entire Papal court to Avignon in the south of France. This was 1309.

Return from exile: Gregory XI & Saint Catherine of Sienna

Philip's capture of the Papacy worked well for him but no so much for the Church, which, bound to French dominance, lost its legitimacy elsewhere. At first the old enemies of Philip, England and Aragon, found it convenient not to have to deal with the Italians in Rome so did not object. However, a succession crisis among Philip IV's heirs led to the English claims on the French throne and outbreak of the Hundred Years War, over which the Avignon Papacy, while maintaining neutrality and assisting in treaty settlements, leaned towards the French side. So when Gregory XI moved the papacy back to Rome in 1376, the French were furious while the English could sit on their hands and shrug, "oh well." No objection them. And no objection, either, from the Holy Roman Emperor, whose brand was quite literally diluted by the move from Rome to Avignon.

Shortly after arriving at Rome, Gregory died. Under the threats from a Roman mob to appoint an Italian, i.e., not a Frenchman, and with disunity and among the French faction, as well as absence of some of the French Cardinals, the Conclave compromised on a bishop from Naples[56], who became Urban VI.

Two years later, with Urban refusing to return to Avignon, the French Cardinals held their own conclave south of Rome at Agnagni, at invitation of the Count thereof, Onorato Caetani, who was angry at Urban VI for removing him from lands appointed to him by Gregory XI.[57] The French Bishops selected a rather complicated man, the son of the Count of Geneva who had studied at the Sorbonne, held a rectory in England, and earned the nickname "Butcher of Cesena" for authorizing the massacre of 3-8,000 people there for the town's participation in a 1377 rebellion against the Papal States (lands directly ruled by the Pope). Now Clement VII (now antipope), he tried to set up shop in Naples, but was chased out of town by a mob who supported the Roman Pope and shouted, "Death to the Antichrist!" Charles V of France, who certainly had a say in Clement's selection, welcomed him back to Avignon and endorsed him as Holy See and gathered support from various regions and countries who preferred France over England, for whatever reason, such as the Scottish who went with whatever the English did not.

Neither of the Avignon papacies were tenable. And no matter how you look at it, Saint Peter died at Rome and not Avignon. Gregory XI seemed to think so, anyway. But he only acted on the conviction at the insistence of Saint Catherine of Sienna (1347-1380).

This time period crosses with that of Saint Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373) who was terribly upset at the Avignon papacy, but whose pleadings were ignored. In 1350, Bridget sought papal authorization for her order, the Bridgettines, but she refused to go to Avignon and went to Rome instead where she awaited the Pope's return -- which occurred finally in 1367 when the Avignon Pope Urban V visited Rome as a symbolic gesture of a permanent return. He ran the Holy See from the Vatican but ran into various problems with local lords who had gotten used to having things there way, rebellions within papal territory (taking advantage of the absence of Rome) as well as having trouble with the bishops back at Avignon who demanded his return. He did grant Saint Bridget her order in 1370. That year, though, as he prepared to return to Avignon, Saint Bridget told him that if he left Rome he would die. He did, and three and a half month slater, he did as Bridget had warned.

Urban's successor, Gregory XI had witnessed Bridget's prophesy to Urban V[58], which may have, I can only imagine, at least been in the back of his mind when he privately vowed before God to return the papacy to Rome should he be selected as Pope. Whatever the intention, for the first years of his papacy there were plenty of fires to put out and reforms to institute, including, interestingly, his 1373 règle d'idiom, which instructed clergy to speak the local vernacular to their flocks outside of the liturgy, which remained in Latin.

Meanwhile, Saint Catherine picked up where Saint Bridget had left off,[59] dictating a series of letters to the Pope commanding him, among things, to return to Rome and in language Gregory characterized as having an “intolerably dictatorial tone, a little sweetened with expressions of her perfect Christian deference.”[60] Not sure if it's Catherine so much as Gregory not wanting to hear it.[61] For example, she wrote,

I have prayed, and shall pray, sweet and good Jesus that He free you from all servile fear, and that holy fear alone remain. May ardor of charity be in you, in such wise as shall prevent you from hearing the voice of incarnate demons, and heeding the counsel of perverse counselors, settled in self-love, who, as I understand, want to alarm you, so as to prevent your return, saying, “You will die.” Up, father, like a man! For I tell you that you have no need to fear.[62]

In 1376, Catherine traveled to Avignon on behalf of the Republic of Florence to negotiate a peace with the Papal States.[63] She failed at the immediate mission[64] but through a divine inspiration won a far more important one: when they met, she told him that she knew of his private vow to return the papacy to Rome.[65] He so decided, but wavered in face of strenuous French objections. When Catherine heard of the indecision, she wrote,

I beg of you, on behalf of Christ crucified, that you be not a timorous child but manly. Open your mouth and swallow down the bitter for the sweet.

In January of 1877, Gregory moved the papacy back to Rome.

Saint Joan questioned on the Schism

By the time of Joan's Trial of Condemnation in 1431, the Western Schism had been officially settled, but the Court tried to use her views on it to discredit her or trip her up. Perhaps thinking that Joan would take the French view of things, she was asked,

What do you say of our Lord the Pope? and whom do you believe to be the true Pope?

To which Joan gave one or her sublime replies,

“Are there two of them?”

Having that one swatted down, the court continued,

Did you not receive a letter from the Count d’Armagnac, asking you which of the three Pontiffs he ought to obey?

Joan replied,

The Count did in fact write to me on this subject. I replied, among other things, that when I should be at rest, in Paris or elsewhere, I would give him an answer. I was just at that moment mounting my horse when I sent this reply.

It's a classic legal maneuver they tried ot pull on her, to lead a witness into a statement, then throw out contrary evidence, in this case, her exchange with the Count. But there was no deceit in Joan, who's testimony was entirely consistent with the evidence. What had happened is that in July 1429, Jean IV, the Count d'Armagnac, himself allied with the English, sent a letter to Joan asking her to clarify the ongoing situation. They got the copies from him. Nevertheless, we have to assume the sincerity of the original letter, as well as the Count's intent: he genuinely thought Joan would provide divine guidance on the situation. As read to the Court at Tours two years later,

My very dear Lady—I humbly commend myself to you, and pray, for God’s sake, that, considering the divisions which are at this present time in the Holy Church Universal on the question of the Popes, for there are now three contending for the Papacy—one residing at Rome, calling himself Martin V., whom all Christian Kings obey; another, living at Paniscole, in the Kingdom of Valence, who calls himself Clement VII[66].; the third, no one knows where he lives, unless it be the Cardinal Saint Etienne and some few people with him, but he calls himself Pope Benedict XIV. The first, who styles himself Pope Martin, was elected at Constance with the consent of all Christian nations; he who is called Clement was elected at Paniscole, after the death of Pope Benedict XIII., by three of his Cardinals; the third, who dubs himself Benedict XIV., was elected secretly at Paniscole, even by the Cardinal Saint Etienne. You will have the goodness to pray Our Saviour Jesus Christ that by His infinite Mercy He may by you declare to us which of the three named is Pope in truth, and whom it pleases Him that we should obey, now and henceforward, whether he who is called Martin, he who is called Clement, or he who is called Benedict; and in whom we are to believe, if secretly, or by any dissembling, or publicly; for we are all ready to do the will and pleasure of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Yours in all things,

Count d’Armagnac.[67]

That outlier third, Benedick XIV[68] was from a city within the Count's territory, so perhaps he was looking to put him down ("who dubs himself"). Or, he really wanted to know what the Maid thought on the matter. It's all very strange, as the Count wrote the letter from Sully in northeastern France, and he was opposed to Charles VII. Joan was inundated with these types of inquiries, by letter or in person.[69]

Joan dictated a reply to the Count's messenger, which is rather clever and to which her testimony at the trial corresponded:

Jhesus Maria. Count d’Armagnac, my very good and dear friend, I, Jeanne, the Maid, acquaint you that your message has come before me, which tells me that you have sent at once to know from me which of the three Popes, mentioned in your memorial, you should believe. This thing I cannot tell you truly at present, until I am at rest in Paris or elsewhere; for I am now too much hindered by affairs of war; but when you hear that I am in Paris, send a message to me and I will inform you in truth whom you should believe, and what I shall know by the counsel of my Righteous and Sovereign Lord, the King of all the World, and of what you should do to the extent of my power. I commend you to God. May God have you in His keeping! Written at Compiègne, August 22nd.

From the trial:

Court: "Is this really the reply that you made?”

Joan: “I deem that I might have made this answer in part, but not all.”[70]

Court: “Did you say that you might know, by the counsel of the King of Kings, what the Count should hold on this subject?”

Joan: “I know nothing about it.”

Court: “Had you any doubt about whom the Count should obey?”

Joan: “I did not know how to inform him on this question, as to whom he should obey, because the Count himself asked to know whom God wished him to obey. But for myself, I hold and believe that we should obey our Lord the Pope who is in Rome. I told the messenger of the Count some things which are not in this copy; and, if the messenger had not gone off immediately, he would have been thrown into the water—not by me, however. As to the Count’s enquiry, desiring to know whom God wished him to obey, I answered that I did not know; but I sent him messages on several things which have not been put in writing. As for me, I believe in our Lord the Pope who is at Rome.”

Must have terribly disappointed the old boys at Rouen and Paris, as a primary reason for their siding with the English and for so vigorously pursuing Joan, as Pernoud discusses, was to affirm their power over the Papacy as well as over the French King.

The Western Schism was settled by granting to the a General Council of bishops the power to remove a Pope from office, which was done with the acquiescence of the Roman Pope, who after removal of the two other competing Popes, himself resigned to be replaced by a Pope selected by the General Council, Martin V.[71] The exercise of power by the Council is known as "conciliarism," which may be seen as

Joan's voices didn't advise her on the issue of the papacy, so, as she said, she spoke for herself. Still, her impact on the issue was significant. A first question is if her reference to "the lord pope who is in Rome" is to Martin V or to Rome as the seat of the Papacy. It appears to be the latter, which would suggest something more than just Joan's "good sense," which the historian Michelet attributed to her authority rather than her voices. Rome had become unstable and subject to mob rule and invasion. It lay at the border of the Kingdom of Naples, which supported the Avignon papacy. Martin V's primary job was to secure and rebuild Rome itself. While subject to the General Council, by restoring the Vatican and the city around it, Martin V laid the foundation for the modern Papacy, which quickly overshadowed conciliarism, which was condemned at the Fifth Lateran Council (1512-1517).

>> here

Joan has no say in any of these affairs, but by coronating Charles VII at Rheims, she secured the necessary monarchical authority for secure Roman Catholic hold on France, be it Gallic in nature. For both Saints Catherine of Sienna and Joan of Arc, the papacy must be seated in Rome. Saint Catherine explicitly sought Christian unity, while Joan led a fight of Christian against Christian, but it was a fight Joan helped to end and not start, and she lamented the loss of life on both sides. A united France for Joan meant a united Church.

Historians correctly attribute the Western Schism to the origins of the Protestant Reformation itself. At the Council of Constance, which ended the schism, Proto-Protestant Catholic priest John Wycliff was posthumously condemned for heresy and his body ordered exhumed and burned, and his follower Jan Hus was defrocked and handed over to hostile secular authority which burned him at the stake. Both men challenged the authority of the Pope -- which brings up a larger question as to which Pope. Wycliff was active before the Western Schism, but wrote his most radical tracts after it. Wycliff would have come of age with fresh memories of previous Schism, as well as with the outbreak of the Hundred Years War. Hus, who received Holy Orders in 1400, was a clear product of the Schism, which had divided the University of Prague where he studied and became master, dean and rector in 1409. Hus' most drastic attacks on the abuses of the papacy were directed at the antipope John XIII who was using (abusing) the authority he (did not) had to collect tithes. In other words, both men were products of a fractured Church that Saints Catherine and Joan sought to repair.

>> Joan swears to Martin >> why ? Martin V, who ended the schism and who started the Univ. at Leuvain, was elected pope on St. Martin's Feast Day. Here for St. Martin: Martin of Tours - Wikipedia

> these two saints admonishsed church unity at Rome ... but the divisions had already set the larger problem that Joan had to save Franch from, Jan Hus ... or his suporters were at th Council of << that settled the 2nd avignon schism.

> Bridget predictd the reduced and exact size of the Vatican in 1922

>> note: the French king withdrew support of avignon in 1398 Antipope Benedict XIII - Wikipedia[72] He was run out of Avignon, but returned w/ great popular support and affirmed by France, Scotland, Castille and Sicily. 1408 Chas VI declared neutrality

< he started the Univ of Glasgw )?( ... then loast France adn had to run from Avignon by 1413 ... then Constance 1415 refused, ws excommnicated in 1417 when Martin came on, ran to Aragon (Tortosa)

>> CHas VII and Pragmatic Sanction << note that a false pragmatic sanction supposedly issued by Saint Louis was circulated when Chas VII was adopting his own. It was not real.

>> councils >> get on Pernoud's obsession w/ them and warning about Joan's opposition to them

> Henry IV > only protestant king of France.. renounced protestantism at St. Denis " "Paris is well worth a mass".

>> House of Valois ended w/ two last (?) kins protesters

Saving Catholicism

We will review here other ways in which Joan characterized her mission as for Catholicism and not just for France, but the larger point is that had Joan not saved France, it may very well have lost its Catholicism under English rule. Had the victor of the Hundred Years War been English and not French, then the King of France during the Protestant reformation would have been English, if not under Henry VIII, likely another. With or without Henry VIII's Anglian church, an English-ruled France would have integrated with the Low Countries and thereby spread its rule into Germany while keeping the rising Spanish power out. Come Martin Luther and the Thirty Years War, we see how tenuous was the hold of the Holy Roman Empire upon Germany and central Europe. By the time the Spanish King seized the Holy Roman Empire, had England ruled France, and had France fallen to Anglicanism, there may not have been much of a Holy Roman Empire left to seize, leaving it, to borrow from Voltaire, "neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire."[73] Papal schisms in the Church leading up to Joan's day made it all inevitable.

Who knows, except that it would have been vastly different. But given the events of the 16th century, one can readily see Roman Catholicism as a victim of an English ruled France and northern Europe. Alternative histories are pure conjecture, as any number of contingencies may have changed the trajectory of an English-ruled France, including the War of Roses which brought Henry VIII's House of Tudor to power in England. Still, we have the plain fact that, as it happened, England separated itself from Rome and France did not, and by saving France from English rule, it was Joan of Arc who caused that possibility.

Jeanne la Pucelle, the Maid

Joan may have been called Petit-Jean, by her family, after her uncle Jean. While we know her in English as Joan of Arc, neither she nor her contemporaries used the surname, d'Arc, which only appeared during investigations after her death in reference to her family, Darc. The name d'Arc arose as one of several varieties of her father's family name, Darc, Dars, Dai, Day, Darx, Dart, or d'Arc.[74] Seems to me that d'Arc is merely the coolest sounding of the batch, so it stuck. Either way, the name Arc is derived from the French for "arrow," which would be fitting for Joan's presence and effect upon her time. A final possibility, though, is that her father's family originated in the village Arc-en-Barrois, which would have made her surname "Arc" or "d'Arc".[75]

Joan testified that girls in her village did not use their paternal surname and instead used that of the mother, and hers was Romée, which makes for an interesting connection in that the name derives from "Rome." The name indicates a pilgrimage to Rome at some point, and thereby becomes interesting to us insofar as at her trial by the English, Joan stood resoundingly for the Roman Pope, whom the English supported, over the schismatic Pope who had been supported by her compatriots in France.

Servant of the Lord

It is said that Joan used the term pucelle, for "maid" or "maiden" to emphasize her virginity.[76] In common usage today the masculine puceau directly means a man who has not had sex. However, the feminine pucelle means either "young girl" (maiden) or "virgin," but not necessarily both, although their association may be implied.[77]

But "maid" or "handmaid," as it could also be translated, makes a clear association not with the greatest virgin of them all, albeit the same person, but the greatest "handmaid" of them all, Our Lady. Joan was devoted to Mary,[78] and had inscribed atop of her battle standard along with that of the Lord: "Jhesus Maria," meaning "Jesus and Mary."[79] Joan would have made a direct connection of the word pucelle to the words of Mary herself:

Mary said, “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word.”[80]

Joan, though, would have known the passage from the Latin Vulgate[81] Bible with the term, ancilla, which is a female servant or slave:[82]

dixit autem Maria ecce ancilla Domini

The Vulgate New Testament was translated from Greek, so we can go to the original Greek word in Luke 1:38, δούλη (doulē), which means "slave woman" or "female servant," both of which become in English, the traditional "handmaiden," the meaning of which is directly "female servant."[83] I'm only concerned about this as historical treatments of Joan ignore the utterly fundamental significance of pucelle in the context of Luke 1:38, Mary's fiat,

May it be done to me according to your word.

The pucelle is not so much a virgin (and Joan was) as God's loyal handmaid who follows the instructions of the angel. For Mary it was the Archangel Gabriel; for Joan it was the Archangel Michael. For both, it was words from God.

Joan the Virgin

To the modern, especially academic, audience, the matter of Joan's virginity is understood as a male obsession or instrument of the patriarchy, or whatever they say about these things. But to both Joan and her accusers, the matter was serious. Joan herself promised her saintly visitors that she would remain a virgin, and to the Court and priests on both sides of Joan's mission, the French Court to see if she was truly an ambassador from God, and the English to try to prove she was a witch, as a virgin, it was understood, was incorrupt of Satan's reach.

According to Michelet's account,

The archbishop of Embrun, who had been consulted, pronounced similarly ; supporting his opinion by showing how God had frequently revealed to virgins, for instance, to the sibyls, what he concealed from men ; how the demon could not make a covenant with a virgin ; and recommending it to be ascertained whether Jehanne were a virgin.[84]

She was then submitted to the physical test conducted by several ladies of the Court who affirmed her purity. It was at least as important as the questions about her theological purity, questions to which she answered consistently, simply, and strenuously. The examiners concluded "The maid is of God."[85] It was also important for fulfillment of the legend that Joan herself invoked at least once, telling her uncle, Durand Lexart,

"Has it not been said that France will be lost by a woman and shall thereafter be restored by a virgin?[86]

At the Condemnation Trial under the English, Joan was pressed several times on her virginity, including as to whether she would stop hearing the voices were she to lose it or if she were to marry (implying loss of virginity). In one instance, the scribe recorded:

Asked whether it had been revealed to her that if she lost her virginity she would lose her good fortune, and that her voices would come no more to her, She said: "That has not been revealed to me." Asked whether she believes that if she were married the voices would come to her, She answered: "I do not know; and I wait upon Our Lord."[87]

This line of questioning becomes rather sinister when Joan is essentially compelled, or tricked, into wearing women's clothes in prison, which turned her into a target of rape by her English guards. She knew that men's clothing that she insisted on wearing kept her safe from the possibility, so it seems to me the Rouen Court was playing into that situation, whereby were she raped, they could say she no longer had her visions. But she refused to answer that question ("I wait upon Our Lord") and, thankfully, while attacked at one point by the guards, it seems she was not actually raped. As for Joan's view of her virginity, it just was what she was, and she promised the Saints that she would stay chaste. Whatever the academics argument that pucelle means maid or virgin or both, we can see from her perspective that her virginity was essential to her mission both as sign of purity and, more importantly, selfless dedication to the Lord. Saint Paul explains it in 1 Corinthians 7:34:

An unmarried woman or a virgin is anxious about the things of the Lord, so that she may be holy in both body and spirit.

Saint Catherine

Nevertheless, Joan's virginity would most importantly signal her connection to Saint Catherine, the virgin martyr. As did Joan, Saint Catherine precociously presented herself to a king, in her case, the Roman Emperor Maxentius, and boldly declared God's message. As did the sitting French ruler, the Dauphin (heir to the throne, but yet called "Dauphin" as he was not yet crowned King) to Joan, Maxentius ordered an inquiry into Catherine by the emperor's finest pagan theologians and philosophers. When these smartest men in the room were confounded by Catherine's theological arguments, the emperor had her imprisoned and tortured. Joan was also submitted to another but entirely antagonistic inquiry at the British-controlled ecclesiastical Court at Rouen that condemned her, but which she confounded with marvelous simplicity and irrefutable logic. Next for Saint Catherine, we have a slight departure from Joan's story, as Maxentius demanded that Catherine marry him and put her to death when she refused.[88] Nevertheless, there is a parallel for Joan, who was put to death after refusing a conciliatory but compromising offer from the court at Rouen.

If you look up Saint Katherine you will see claims that she never existed, or that the stories about her are medieval fabrications.[89] But that's not how God works. God love types and bookends, and Saint Joan is clearly a "type" of Saint Catherine: When the Dauphin ordered the church inquiry, no one was thinking, "My, that's just what happened to Saint Catherine!" And no such thoughts arose when the court at Rouen tried to force her into admission of heresy by showing her torture machines and then tricking her into signing a document to renounce her visions and to wear women's clothing -- at which point her captors tried to rape her. The very typology of Saint Catherine. And Joan was also visited by Saint Margaret, another virgin and maiden martyr who was killed after refusing to marry a Roman governor and refusing to renounce her faith. The very typology of Joan.

Joan was not mimicking Saints Catherine and Margaret, she was following them directly.

What'd Joan actually do?

It's hard to say what Saint Joan most accomplished, as her episodes are interconnected and woven backwards and forwards. To save France, she needed to crown the Dauphin legitimate King of France; to crown the King, she needed to take the city of Orleans; to take the city of Orleans, she needed the support of the Dauphin (and the French court); to get the support of the Dauphin she needed to prove that she could lead the army. In other words, she re-organized the entire French political and military order.

To those ends, three accomplishments stand out:

- She generated tremendous enthusiasm from the public, which forced the French court to support her;

- She breathed confidence into the French army, which had been browbeaten and self-defeating until her leadership inspired them; and

- She scared the crap out of the English.[90]

As to that last, we know just how much she scared them. From a letter to the King of England by one of his generals,

a greet strook upon your peuple that was assembled there [at Orleans] in grete nombre, caused in grete partie, as y trowe, of lakke of sadded believe, and of unlevefull doubte that thei hadded of a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle, that used fals enchauntements and sorcerie. The which strooke and discomfiture nought oonly lessed in grete partie the mobre of youre people.

Translation: she's a witch![91]

Her mission, though, had two parts: take Orleans first, then crown the king at Rheims. The importance of Orleans is easy to understand, as it saved France militarily. But why the need for the coronation at Rheims? Sure, it was the traditional site of French coronations, and so held symbolic value. But let's try to think like God for a moment (try), and it becomes clearer.

The Dauphin, as Joan called the Prince, was already King of France. He had been duly crowned at

Joan didn't realize it, but once the King of France was duly crowned, her work was done. It's a very sad period in which, hampered by hedging and outright delays from the Court and military heads, she demands movement, and now, but got next to nothing in reply. With only a core of supporters, a fantastic group who play an important role in the eventual defeat of the English, Joan fails to take Paris and is captured at a minor battle soon after. She spends the next year shuffled between castles and prisons, and is fed up to the English who use a French ecclesiastic court to try her for heresy in a rigged show trial.

Her greatest act was to liberate Orléans, and her greatest accomplishment was the eventual victory of France over England to end the Hundred Years War, but her greatest moment was her martyrdom on the stake, repeating the word, "Jesus." Her greatest legacy was an ongoing, Catholic France.

Catholic Joan

Given most biographies and depictions of Joan, it's rather hard to realize her Catholicism. But she was fundamentally, authentically and thoroughly Catholic. Father Jean Massieu recalled that during her trial at Rouen under the English, Joan genuflected before the consecrated Host that lay behind even closed doors:

Once, when I was conducting her before the Judges, she asked me, if there were not, on her way thither, any Chapel or Church in which was the Body of Christ. I replied, that there was a certain Chapel in the Castle. She then begged me to lead her by this Chapel, that she might do reverence to God and pray, which I willingly did, permitting her to kneel and pray before the Chapel; this she did with great devotion. The Bishop of Beauvais was much displeased at this, and forbade me in future to permit her to pray there.

and,

And, besides, as I was leading Jeanne many times from her prison to the Court, and passed before the Chapel of the Castle, at Jeanne’s request, I suffered her to make her devotions in passing; and I was often reproved by the said Benedicite, the Promoter, who said to me “Traitor! what makes thee so bold as to permit this Excommunicate to approach without permission? I will have thee put in a tower where you shall see neither sun nor moon for a month, if you do so again.”

The Bishop of Beauvais' anger at her prayer before the chapel was recognition of her Catholic authenticity, which was his job to deny. Perhaps he truly believed her to be a witch and a heretic, but he simply could not stand for her presentation as a true and faithful Catholic, which is why her worship, on learning that the Lord was present[92] in the chapel, so angered him.

Joan's mother taught her to recite in Latin the Our Father, Ave Maria, and Credo prayers. Her military standard read, "Jhesus Maria," and her final words were "Jesus" repeated as the flames consumed her and while staring at a cross she asked be held before her.

Skeptics say she was merely conforming to norms of her day. Sorry, she believed and she converted many.

Young Saint Joan

Let's next place Saint Joan's birthplace within the context of the story.

Domrémy

Joan's village lay along the upper Meuse River. The village was geographically in the province of Lorraine but was politically under the Duchy of Bar by the time of Joan's birth, indicative of the transient nature of medieval borders and allegiances. At Domrémy the Meuse was yet a small river, but significant enough to contain an island that Joan's father once negotiated to use to protect and hide the villagers and their livestock during military raids[93] during the ongoing civil war between French factions and the overall Hundred Years War between the French and English.

The people of Domrémy were loyal to the French cause, which supported the son of Charles VI, Louis, the Dauphin, or heir to the throne. Louis, however, was disinherited by his father, who through a marriage gave the royal succession to the English King, Henry V. (More on all that below.) Domrémy itself was politically and economically unimportant, but it was mixed up in the ongoing war that went on around it, on the periphery but susceptible to raids, cross-alliances, etc.

Another town near to Domrémy that was important to the story of Saint Joan is Vaucouleurs, which lay along the Meuse to the north. Vaucouleurs was loyal to the French cause, but was precariously located near disputed lands between France, Burgundy and the Holy Roman Empire. The town was fortified and held by a French garrison led by Captain Robert de Baudricourt. It is unclear to me how, exactly, Baudricourt maintained his position against the Burgundians and the English, but there was a lot of horse trading and paid protection going on, so it was likely due to adept negotiations as well as his fortifications.[94] Or, there was something divine going on here, as Baudricourt's loyalty to the Dauphin was necessary for Joan's introduction to him.[95]

By the time Baudricourt met Joan, he had already assigned official control of the city to the Burgundian, Antoine de Vergy, but had not yet handed it over to him. Ultimately, and despite being surrounded by Burgundian controlled-territory, Baudricourt never actually ceded the city, although he was forced into a a pledge of neutrality. (Don't play poker with Baudricourt.)

Given that with God there are no coincidences, a similar surrender to that which Baudricourt refused to conclude (through Joan's inspiration?), was accepted by one Pierre Cauchon, from the town of Vitry, from our friend Étienne de Vignolles, who will be known to us in the story of Saint Joan as "La Hire," one of Joan's most loyal commanders and a key warrior in the ultimate French victory. Cauchon, a French Bishop and English-loyalist, was the very guy who orchestrated Joan's execution. Rather odd, these alignments -- or not.[96]

Across the region where Joan grew up, a map of loyalties would look like Swiss cheese, or, to be more French, a melted Camembert, with pockets and shoots of loyalties across the various regions. Domrémy, Vaucouleurs, and the all-important Rheims, where Joan needed Charles VII to be coronated, were all held by French-loyalist, mostly the Armagnac faction under the House of Orléans, who opposed the Burgundians under the House of Burgundy.[97] The Duke of Burgundy, meanwhile, held Paris, Troyes, Burgundy, and Flanders (his economic base) and pockets of lands or loyalties across Champagne and Bar.

Three towns of importance to Joan's story prior to leaving the region to meet with the Dauphin (and onward to save France), Domrémy, Vaucouleurs, and Neufchâteau, were all on the border or edge of these opposed loyalties, principally because they were all along the upper Meuse, which was held by Armagnac faction French loyalists.[98] When Joan's home village, Domrémy, was pillaged by Burgundian forces, it was part of an operation ordered by the English to take the loyalist garrison at Vaucouleurs.[99]

The Burgundian hold of Paris and other areas of northern France was due to the English military presence, so it was an alliance that was mutually beneficial but not mutual in purpose. For example, the English needed to hold Paris to maintain their claim on the French crown, but they also needed the Burgundians to administer and defend it.

Had the English managed to push south of Orléans, an Armagnac stronghold and seat of the normal heir to the French throne, the Duke d'Orléans (who was imprisoned in England at the time), they would have very likely taken all of France and enforced the Treaty of Troyes, which gave French succession to the English. Defending Orléans was the Duke's half brother, John the Bastard[100], who arrived to the city in October of 1428. He huddled the people inside the city walls, abandoning buildings and churches outside the boundaries. A deal was proposed, not by the Bastard, but by terrified citizens of Orléans, to the Duke of Burgundy that would yield the city to him while upholding its neutrality. Ordered by the English, the Duke refused it. Meanwhile within Orléans, desperation set in, especially following the French humiliation at the Battle of the Herrings on February 12 (the outcome of which Joan had predicted to Captain Baudricourt at Vaucouleurs).

Soon after the Battle of Herrings, as things seemed to be falling apart, the Bastard received news of a mysterious "maid" who was going to rescue the city of Orléans. He was curious. He had recieved some reinforcements, but the situation was dire. He wrote,

It is told that there had lately passed through the town of Gien a maid [une pucelle], who proclaimed that she was on her way to Chinon to the gentle Dauphin, and said that she had been sent by God to raise the siege of Orléans and take the King to his anointing at Reims.[101]

So he sent emissaries to the King's court to see what was going on.

The peasant

Joan was a peasant girl, but not just a peasant girl.[102] Her father, Jacques Darc, owned about 50 acres of land for cultivation and grazing and a house big and furnished enough to house visitors. He served as the Domrémy village doyen, which included responsibility to announce decrees of the village council, run village watch over prisoners and the village in general, collect taxes and rents, supervise weights and measures, and oversee production of bread and wine. He was not an inconsiderable man, although he was at best a big man in a very small village.[103]

Her mother was more formidable, coming from a modest but better off family. It was she, Isabelle Romée, who after Joan's death championed her to the Church and French government and forced the reassessment of the her condemnations and execution. The name, which Joan indicated was her surname (and not her father's), as girls in her region went by their maternal family name. If so, the name Romée indicates somewhere in the line a connection to Rome, likely through a pilgrimage at some point.[104] The name of the village itself, Domrémy, has an interesting connection to its possible Roman origin, Domnus Remigius, which placed it under the Archbishop of Rheims, St. Rémi, who baptized Clovis -- thus circling back to a fundamental goal of Saint Joan to coronate the King of France, Charles VII, at Rheims where Clovis was baptized and Philip II coronated. (At the hand of God, there are no coincidences.)

Joan grew up in this little village with her primary role to tend the farm and household and to spin wool. She tended the animals when she was younger but not much, she testified, after she reached "the age of understanding." She likely also helped with sewing and harvesting the fields.[105]

To summarize, the young Saint Joan was illiterate, unschooled in all but the lessons of farming, wool spinning, Church, and local lore. She seems to have had a happy childhood growing up with other children who played together, joined village festivals, and went to Church every week. I like this description of her childhood from Butler's 1894 "Lives of Saints,"

While the English were overrunning the north of France, their future conqueror, untutored in worldly wisdom, was peacefully tending her flock, and learning the wisdom of God at a wayside shrine.[106]

It all changed when she was thirteen and was visited by the Archangel Saint Michael who told her from the beginning that she must go to "France" -- and to church, which she The children noticed that she withdrew from their games and prayed constantly, and urged them all to go to Church. Joan testified,

"Since I learned that I must come into France , I took as little part as possible in games or dancing.

From then on, it was a matter of instruction and timing.

God's will be done

We all know from the Lord's Prayer,

Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven

and Jesus' prayer at the Garden,

Not my will but yours

<< confirm

Joan's journey is not so much fulfillment of God's will as her acceptance of it. Every step, every decision was God's will not hers.

What's additionally remarkable is her insistence upon delivering messages of warning and pleas for surrender of the English. Twice << before the Battle of Orleans Joan spoke to the English across the field to implore them to surrender and go away. They ridiculed her (reverse Monty Python scene) and her own military counselors deplored it. But why?

God wants us -- requires us -- to choose him. As his instrument, Joan gave the English the opportunity to choose

Mission from God

Victory at Orléans

Of all the revisions, diversions, and distortions of Saint Joan's story and legacy, I don't think any of them mention that another woman, Yolanda, Queen of Sicily played a crucial role in the story. Yolanda was the Dauphin's mother-in-law. She, too, must have believed the Maid, because she personally financed the campaign on Orléans. That's no small thing, but it is rarely mentioned.[107]

A next character to introduce is the Archbishop of Rheims, Regnault of Chartres, and Chancellor of France. At best, he distrusted Joan, at worst he resented or even loathed her. He was not her friend. Regnault and the Court council had ordered the Bastard to lead Joan's army away from Orléans to take Chécy. The idea was to present a diversion to the English at Orléans. Joan was furious.

Are you the Bastard of Orléans?

Yes, I am, and I rejoice your coming.

Are you the one who gave orders for me to come here, on this side of the river so that I could not go directly to Talbot [English commander] and the English?

John the Bastard explained that the "wisest" men around him had advised the action.

In God's name, the counsel of Our Lord God is wiser and safer than yours. You thought that you could fool me, and instead you fool yourself; I bring you better help than ever came to you from any soldier to any city: It is the help of the King of Heaven. This help comes not for love of me but from God Himself, who at the prayer of St. Louis and of St. Charlemagne has had pity on the city of Orléans. He has not wanted the enemy to have both the body of the lord of Orléans and his city.

Joan there goes for it -- Saints Louis and Charlemagne? These are not just founders of France, these are the founders of Catholic France.

To the Bastard's surprise, and in support of an order from Joan to move supplies by the river, the winds changed, allowing for the operation. The army crossed the Loire and entered the besieged city, which was stirred up and hopeful, finally. But Joan was forced to wait as the French army gathered and prepared. During this time, she wanted out to an embankment and yelled at the English to go home. They replied with insults[108], including one from an English commander that she was a "cowherd" and would be burned at the stake.

Impatient, impetuous, and sure, Joan was frustrated at the delays. Finally, some skirmishes commenced, with Joan leading one that took an English embankment. It was a small victory, but the first by the French, and invigorating for them. Joan, for her part, was dismayed by the violence, and prayed ceaselessly for the souls of her fallen soldiers, especially those who she feared had not confessed before their deaths. On Ascension Thursday, she sent a third letter of warning to the English to go home, signed

Jesus-Maria Joan the Maid

Marvelous![109] Since the English had held her herald who brought the first two letters, she sent the last by arrow. They English shouted, "Here's news from the whore of the Armagnacs!", which greatly distressed her. Against various opinions, Joan ordered an assault, finally, and pushed the English back from a second fortification that they had moved to from a first which they abandoned. They were worried. The French commanders, though, exercised their usual defeatism, and begged Joan to just hold the city behind it's fortifications. Joan replied,

Get up tomorrow very early in the morning, earlier than you did today, and do the best you can; keep cose to me, for tomorrow I will have much to do, more than I have ever done before; and tomorrow blood will leave my body above my breast.

Joan led the assault, receivied an arrow in her upper chest, had it treated (without charms, as suggested, which she said would be sinful), and returned to the fight. An impasse followed, and even La Hire wanted to retire. Joan said, no, wait, and prayed in a nearby vineyard for about fifteen minutes. Then she grabbed her standard from her squire, and rushed towards the English embankment. The French army spontaneously erupted in a charge to follow her and took the English stronghold. Orléans was saved.[110] Joan's biographer makes an interesting notation following the description of the battle that the people of Orléans, who had been traumatized and abused by men at arms throughout the Hundred Years War, especially the mercenaries of one side or the other of the Armagnac-Burgundian civil war, received the army in celebration and joy:

Under the command of the Maid, even warfare had briefly changed its face back to a world of honor[111]

Visions not delusions

From the transcript of the Trial of Condemnation at Rouen in 1431, "Thursday, March 1st, in the same place, the Bishop and 58 Assessors present":

“Since last Tuesday, have you had any converse with Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret?”

“Yes, but I do not know at what time.”

“What day?”

“Yesterday and to-day; there is never a day that I do not hear them.”

“Do you always see them in the same dress?”

“I see them always under the same form, and their heads are richly crowned. I do not speak of the rest of their clothing: I know nothing of their dresses.”

“How do you know whether the object that appears to you is male or female?”

“I know well enough. I recognize them by their voices, as they revealed themselves to me; I know nothing but by the revelation and order of God.”

“What part of their heads do you see?”

“The face.”

“These saints who shew themselves to you, have they any hair?”

“It is well to know they have.”

“Is there anything between their crowns and their hair?”

“No.”

“Is their hair long and hanging down?”

“I know nothing about it. I do not know if they have arms or other members. They speak very well and in very good language; I hear them very well.”

“How do they speak if they have no members?”

“I refer me to God. The voice is beautiful, sweet, and low; it speaks in the French tongue.”

“Does not Saint Margaret speak English?”

“Why should she speak English, when she is not on the English side?”[112]

Joan first met Saints Margaret and Catherine back at Domremy

Several events from her village life stand out. These pieces fall together for the launch of Joan's mission to save France (and/or Catholicism -- more on that later). They are seen by skeptics as to obvious to be true and so fabrications. But if you think about it, her trajectory is entirely contingent upon them, so rather than presenting evidence of fabrication, they are strong proofs:

- Saint Michael is patron Saint and savior of France, and Saints Catherine and Margaret were actively venerated in the region;

- Joan's visions started after a raid on her village by an English ally, the Burgundian Henri d'Orly[113] (note that Joan's village of Domrémy was located within territory controlled by the English-allied Burgundians and outside of the control of the Dauphin, the French claimant on the throne);

- A young man in the village claimed she was betrothed to him;

- An old beech tree in a grove by the village was said to be occupied by fairies, which village children;[114]

- Local legends held that an armed virgin or a virgin carrying a banner would save France[115]'

It would make absolutely no sense if Joan had come from a place or experience removed from any of the above. Rather than causing her visions, an assertion for which there is no evidence and that is based solely on rejection of divine inspiration, these contingencies affirmed and supported what the visions told her. The honest observer must accept the clear, incredibly well-documented historical facts of Joan's era, much of which was predicted in her visions. So those who deny her mission as divinely guided can only fall back on the idea that, heh, her visions were not real, but she thought they were, and that's what counts.[116]

For example, as for legends of a virgin savior of France, Joan probably knew of them all. But one, in particular was both more recent and more directly about Joan -- and she understood it early on to be about her. She had not told her parents or the local priest about her visions, which had been going on for several years.

The timeline here is interesting. From the beginning, her voices told her she would go to "France."[117] At some point, she was told specifically to go to Vaucouleurs and speak to Robert de Baudricourt, captain of the guards, who would take her to the Dauphin. By then, she was very clear on her mission, it's purpose and outcome. She told her uncle, whom she asked to introduce her to Baudricourt,

to ask him to lead her to the place where my dauphin was