Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431) called herself, Jeanne la Pucelle[1], meaning "Joan the Maid." Joan is feminine for John, which means "God favors." Most appropriate. She was later called "Joan of Orleans," or "the Maid of Orleans," for her miraculous intervention in the One Hundred Years War, the turning point of which was the "Siege of Orleans," conducted under Joan's brilliant military command. She saved France, and doing so likely saved Catholicism itself, which may well have been her mission all along. She was canonized by the Catholic Church in 1920.

This page presents the facts of the life and accomplishments of Saint Joan of Arc, as well as the historical context. It offers commentary and criticism of historical and academic views of Joan, especially as regards the secularization and feminization of her legacy. Herein is a Catholic view of Saint Joan, and without apology.

** page under construction **

| DATE | EVENT | NOTES |

|---|---|---|

| 100 Years War between France and England starts | Not a continuous war, but a series of events, battles, alliances, treaties, etc. that decided control of France | |

| 1412 | Jeanne born to Jaque and Isabelle Darc | Her birth date was given by a contemporary as Feb 12, but she never claimed that day |

| Jan 6 | Joan's birthdate corresponding to the Epiphany. | Per a contemporary but never affirmed by Joan |

| 1415 | Battle of Agincourt (overwhelming English victory) | Henry V of England re-asserts English claims on France and commences accumulation of territory in northern France |

| 1418 | The French Burgundian faction seizes Paris | |

| 1419 | Burgundian alliance with the English | |

| 1420 | Treaty of Troyes gives French succession to English King Henry V | the English maintain their claim on the French throne through the infant king, Henry VI, who assumed the title upon the death of French King Charles VI. He would be crowned King of France in Paris in 1431 under English-Burgundian control of the city. |

| 1422 | Charles VI of France and Henry V of England die; | |

| 1425 | ||

| Summer | Joan experiences her first visions, starting with the Archangel Michael and then with Saints Catherine and Margaret | Joan said she was 13, so the year depends on assumptions of her birth year |

| Joan's first vision with St. Michael the Archangel | ||

| 1428 | ||

| May | Joan's father allows her to visit a cousin at Burey-le-Petit, who was expecting | the location was near to Vaucouleurs, to where her uncle brought her |

| May 13 | Joan travels to Vaucouleurs and meets Robert de Baudricourt, who rebuffs her. | Coincides with the Feast of the Ascension of the Lord |

| June | Domreme raided by Burgundian forces and burnt and ransacked. | Domréme villagers flee to Neufchateau for protection from bandits; there, a man sues Joan for breach of marital contract |

| July | Joan and her family escape to Neufchâteau and stay with "la Rousse" for | |

| Oct 12 | The siege of Orleans begins | |

| Fall | Joan again travels to Vaucouleurs to meet Robert de Baudricourt who this time agrees to help her to meet the Dauphin. | or possibly in Jan 1429 |

| 1429 | ||

| Jan | Joan returns to Vaucouleurs and is again rejected by Baudricourt | Joan says "farewell" to a friend |

| Joan tells Baudricourt the French would lose another battle. He rebuffs her again and she goes home. | ||

| Feb 12 | French forces lose the Battle of the Herrings | The French had attacked an English supply convoy that was carrying salted herring to their troops at Orléans. |

| Feb 22 | Joan returns and Baudricourt, now convinced by her prediciton of the Battle of Herrings, agrees to send Joan to see the Dauphin | |

| February | Joan travels to Chinon to meet the Dauphin | She is escorted by guards from Vaucouleurs |

| Joan meets the Dauphin | ||

| Mar 22 | Joan dictates a letter of warning to the English King | See |

| Siege of Orleans lifted under Joan's leadership | ||

| April 29 | Joan prays at the Cathedral of Orleans | |

| 1429 | Dauphin crowned | |

| 1430 | ||

| May | Joan taken prisoner by Duke of Luxumbourg | |

| Charles VII refuses to pay her ranson | ||

| English pay the ranson and she is transferred to Rouen | ||

| 1431 | ||

| Feb 21 | Joan's show trial at Rouen commences | |

| May 24 | Joan signs the abjuration document | |

| May 28 | Joan rescinds her abjuration | |

| May | Joan is convicted of heresy in ecclesiastical court | |

| May 30 | Joan is burned at the stake | |

| 1456, July 7 | The conviction is invalidated and Joan is declared a martyr for France | |

| 1905, April 11 | Joan beatified by Pope Pius X | |

| 1920, May 16 | Saint Joan canonized by Pope Benedict XVI | |

Jeanne la Pucelle

Joan may have been called Petit-Jean, by her family, after her uncle Jean. While we know her in English as Joan of Arc, neither she nor her contemporaries used the surname, d'Arc, which only appeared during investigations after her death in reference to her family, Darc. The name d'Arc arose as one of several varieties of her family name, Darc, Dars, Dai, Day, Darx, Dart, or d'Arc.[2] Seems to me that d'Arc is merely the coolest sounding of the batch, so it stuck. Either way, the name Arc is derived from the French for "arrow," which would be fitting for Joan's presence and effect upon her time. A final possibility, though, is that her father's family originated in the village Arc-en-Barrois, which would make him d''Arc, or "of Arc".[3]

Joan testified that girls in her village did not use their paternal surname and instead used that of the mother, and hers was Romée, which makes for an interesting connection in that the name derives from "Rome", indicating a pilgrimage to Rome at some point, and which becomes interesting to us insofar as at her trial by the English, Joan stood resoundingly for the Roman Pope, whom the English supported, over a schismatic Pope who had been supported by her compatriots in France.

Joan used the term pucelle, for "maiden," to emphasize her virginity and purity, and, perhaps, to emphasize her connection to Saint Catherine, the virgin and maiden martyr.[4] As did Joan, Saint Catherine precociously presented herself to a king, in her case, the Roman Emperor Maxentius, and boldly declared God's message. As did the sitting French ruler, the Dauphin (heir to the throne, but yet called "Dauphin" as he was not yet crowned King) to Joan, Maxentius ordered an inquiry into Catherine by the emperor's finest pagan theologians and philosophers. When these smartest men in the room were confounded by Catherine's theological arguments, the emperor had her imprisoned and tortured. Joan was also submitted to another but entirely antagonistic inquiry at the British-controlled ecclesiastical Court at Rouen that condemned her, but which she confounded with marvelous simplicity and irrefutable logic. Next for Saint Catherine, we have a slight departure from Joan's story, as Maxentius demanded that Catherine marry him and put her to death when she refused.[5] Nevertheless, there is a parallel for Joan, who was put to death after refusing a conciliatory but compromising offer from the court at Rouen.

If you look up Saint Katherine you will see claims that she never existed, or that the stories about her are medieval fabrications.[6] But that's not how God works. God love types and bookends, and Saint Joan is clearly a "type" of Saint Catherine: When the Dauphin ordered the church inquiry, no one was thinking, "My, that's just what happened to Saint Catherine!" And no such thoughts arose when the court at Rouen tried to force her into admission of heresy by showing her torture machines and then tricking her into signing a document to renounce her visions and to wear women's clothing -- at which point her captors tried to rape her. The very typology of Saint Catherine. And Joan was also visited by Saint Margaret, another virgin and maiden martyr who was killed after refusing to marry a Roman governor and refusing to renounce her faith. The very typology of Joan.

Joan was not mimicking Saints Catherine and Margaret, she was following them directly.

What'd Joan actually do?

It's hard to say what Saint Joan most accomplished, as her episodes are interconnected and woven backwards and forwards. To save France, she needed to crown the Dauphin legitimate King of France; to crown the King, she needed to take the city of Orleans; to take the city of Orleans, she needed the support of the Dauphin (and the French court); to get the support of the Dauphin she needed to prove that she could lead the army. In other words, she re-organized the entire French political and military order.

To those ends, three accomplishments stand out:

- She generated tremendous enthusiasm from the public, which forced the French court to support her;

- She breathed confidence into the French army, which had been browbeaten and self-defeating until her leadership inspired them; and

- She scared the crap out of the English.

As to that last, we know just how much she scared them. From a letter to the King of England by one of his generals,

a greet strook upon your peuple that was assembled there [at Orleans] in grete nombre, caused in grete partie, as y trowe, of lakke of sadded believe, and of unlevefull doubte that thei hadded of a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle, that used fals enchauntements and sorcerie. The which strooke and discomfiture nought oonly lessed in grete partie the mobre of youre people.[7]

Translation: she's a witch! (See the reference note for full modern English translation.)

Joan didn't realize it, but once the King of France was duly crowned, her work was done. It's a very sad period in which, hampered by hedging and outright delays from the Court and military heads, she demands movement, and now, but nothing. With only a core of supporters, a fantastic group who play an important role in the eventual defeat of the English, Joan fails to take Paris and is captured at a minor battle soon after. She spends the next year being shuffled between castles and prisons, and is fed up to the English who use a French ecclesiastic court to try her for heresy in a rigged show trial.

Her greatest act was to liberate Orléans, and her greatest accomplishment was the eventual victory of France over England to end the Hundred Years War, but her greatest moment was her martyrdom on the stake, repeating the word, "Jesus."

God works this way.

Catholic Joan

It's rather hard to realize her Catholicism, given most biographies and depictions of her. But she was fundamentally, authentically and thoroughly Catholic.

Father Jean Massieu recalled that during her trial under the English,

Once, when I was conducting her before the Judges, she asked me, if there were not, on her way thither, any Chapel or Church in which was the Body of Christ. I replied, that there was a certain Chapel in the Castle. She then begged me to lead her by this Chapel, that she might do reverence to God and pray, which I willingly did, permitting her to kneel and pray before the Chapel; this she did with great devotion. The Bishop of Beauvais was much displeased at this, and forbade me in future to permit her to pray there.

and,

And, besides, as I was leading Jeanne many times from her prison to the Court, and passed before the Chapel of the Castle, at Jeanne’s request, I suffered her to make her devotions in passing; and I was often reproved by the said Benedicite, the Promoter, who said to me “Traitor! what makes thee so bold as to permit this Excommunicate to approach without permission? I will have thee put in a tower where you shall see neither sun nor moon for a month, if you do so again.”

The Bishop of Beauvais' anger at her genuflection before the chapel was recognition of her authenticity. Perhaps he truly believed her to be a witch and a heretic, but he simply could not stand for her presentation as a true Catholic, which is why her worship, on learning that the Lord was present (i.e. consecrated bread was there) outside -- outside -- the chapel so angered him.

Joan was Catholic.

Her mother taught her to recite in Latin the Our Father, Ave Maria, and Credo prayers. Her military standard read, "Jesus and Mary," and her final words were "Jesus," which she repeated as the flames consumed her and while staring at a cross she asked be held before her.

Skeptics say she was merely conforming to norms of her day. Sorry, she believed and she converted many.

Young Saint Joan

Let's next place Saint Joan's birthplace within the context of the story.

Domrémy

Joan's village lay along the Meuse River not far from its source. The village was geographically in the province of Lorraine but was politically under the Duchy of Bar by the time of Joan's birth, indicative of the transient nature of medieval borders and allegiences. At Domrémy the Meuse was yet a small river, but significant enough to contain an island that Joan's father once negotiated to use to protect and hide the villagers and their livestock during military raids during the ongoing civil war between French factions and the overall One Hundred Years War between the French and English.

The people of Domrémy were loyal to the French cause, which supported the son of Charles VI, Louis, the Dauphin, or heir to the throne. Louis, however, was disinherited by his father, who through a marriage gave the royal succession to the English King, Henry V. (More on all that below.) Domrémy itself was politically and economically unimportant, but it was mixed up in the ongoing war that went on around it, on the periphery but susceptible to raids, cross-alliances, etc.

Another town near to Domrémy that was important to the story of Saint Joan is Vaucouleurs, which lay along the Meuse to the north. Vaucouleurs was loyal to the French cause, but was precariously located near disputed lands between France, Burgundy and the Holy Roman Empire. The town was fortified and held by a French garrison led by Captain Robert de Baudricourt. It is unclear to me how, exactly, Baudricourt maintained his position against the Burgundians and the English, but there was a lot of horse trading and paid protection going on, so it was likely due to adept negotiations as well as his fortifications.

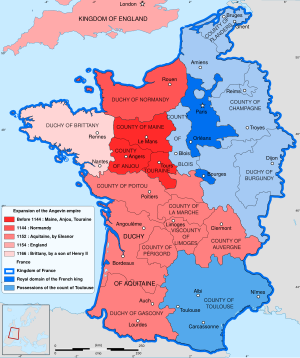

A map of loyalties across the region would look like Swiss cheese, or, to be more French, a melted Camembert, with pockets and shoots of loyalties across the various regions. Domrémy, Vaucouleurs, and the all-important Rhiems (or Riems), where Joan needed Charles VII to be coronated, were all held by French-loyalist, mostly the Armagnac faction under the House of Orléans, who opposed the Burgundians under the House of Burgundy.[8] The Duke of Burgundy, meanwhile, held Paris, Troyes, Burgundy, and Flanders (his economic base) and pockets of lands or loyalties across Champagne and Bar. Three towns of importance to Joan's story prior to leaving the region to meet with the Dauphin (and onward to save France), Domrémy, Vaucouleurs, and Neufchâteau were all on the border or edge of these opposed loyalties, principally because they were all along the upper Meuse, which was held by the French loyalists, the Armagnac faction.[9] When Joan's home village, Domrémy, was pillaged by Bugundian forces, it was part of an operation, ordered by the English, to take the loyalist garrison at Vaucouleurs.[10]

The Burgundian hold of Paris and other areas of northern France was due to the English military presence, so it was an alliance that was mutually beneficial but not mutual in purpose. For example, the English needed to hold Paris to maintain their claim on the French crown, but they also needed the Burgundians to administer and defend it.

Had the English managed to push south of Orléans, an Armagnac stronghold and seat of the normal heir to the French throne, the Duke d'Orléans (who was imprisoned in England at the time), they would have very likely taken all of France and enforced the Treaty of Troyes which gave French succession to the English. As it was, the English began their attack upon Orléans in 1428, with a siege of the city that was broken by Saint Joan.

Young Saint Joan

Joan was a peasant girl, but not just a peasant girl.[11] Her father, Jacques Darc, owned about 50 acres of land for cultivation and grazing and a house big and furnished enough to house visitors. He served as the Domrémy village doyen, which included responsibility to announce decrees of the village council, run village watch over prisoners and the village in general, collect taxes and rents, supervise weights and measures, and oversee production of bread and wine. He was not an inconsiderable man, although he was at best a big man in a very small village.[12]

Her mother was more formidable, coming from a modest but better off family. It was she, Isabelle Romée, who after Joan's death championed her to the Church and French government and forced the reassessment of the her condemnations and execution. The name, which Joan indicated was her surname (and not her father's), as girls in her region went by their maternal family name. If so, the name Romée indicates somewhere in the line a connection to Rome, likely through a pilgrimage at some point.[13] The name of the village itself, Domrémy, has an interesting connection to its possible Roman origin, Domnus Remigius, which placed it under the Archbishop of Rhiems, St. Rémi, who baptized Clovis -- thus circling back to a fundamental goal of Saint Joan to coronate the King of France, Charles VII, at Rhiems where Clovis was baptized and Philip II coronated. (At the hand of God, there are no coincidences.)

Joan grew up in this little village with her primary role to tend the farm and household and to spin wool. She tended the animals when she was younger but not much, she testified, after she reached "the age of understanding." She likely also helped with sewing and harvesting the fields.[14]

To summarize, the young Saint Joan was illiterate, unschooled in all but the lessons of farming, wool spinning, Church, and local lore. She seems to have had a happy childhood growing up with other children who played together, joined village festivals, and went to Church every week. I like this description of her childhood from Butler's 1894 "Lives of Saints,"

While the English were overrunning the north of France, their future conqueror, untutored in worldly wisdom, was peacefully tending her flock, and learning the wisdom of God at a wayside shrine.[15]

It all changed when she was thirteen and was visited by the Archangel Saint Michael who told her from the beginning that she must go to "France" -- and to church, which she The children noticed that she withdrew from their games and prayed constantly, and urged them all to go to Church. Joan testified,

"Since I learned that I must come into France , I took as little part as possible in games or dancing.

From then on, it was a matter of instruction and timing.

Visions not delusions

Several events from her village life stand out. These pieces fall together for the launch of Joan's mission to save France (and/or Catholicism -- more on that later). They are seen by skeptics as to obvious to be true and so fabrications. But if you think about it, her trajectory is entirely contingent upon them, so rather than presenting evidence of fabrication, they are strong proofs:

- Saint Michael is patron Saint and savior of France, and Saints Catherine and Margaret were actively venerated in the region;

- Joan's visions started after a raid on her village by an English ally, the Burgundian Henri d'Orly[16] (note that Joan's village of Domrémy was located within territory controlled by the English-allied Burgundians and outside of the control of the Dauphin, the French claimant on the throne);

- A young man in the village claimed she was betrothed to him;

- An old beech tree in a grove by the village was said to be occupied by fairies, which village children;[17]

- Local legends held that an armed virgin or a virgin carrying a banner would save France[18]'

It would make absolutely no sense if Joan had come from a place or experience removed from any of the above. Rather than causing her visions, an assertion for which there is no evidence and that is based solely on rejection of divine inspiration, these contingencies affirmed and supported what the visions told her. The honest observer must accept the clear, incredibly well-documented historical facts of Joan's era, much of which was predicted in her visions. So those who deny her mission as divinely guided can only fall back on the idea that, heh, her visions were not real, but she thought they were, and that's what counts.[19]

For example, as for legends of a virgin savior of France, Joan probably knew of them all. But one, in particular was both more recent and more directly about Joan -- and she understood it early on to be about her. She had not told her parents or the local priest about her visions, which had been going on for several years.

The timeline here is interesting. From the beginning, her voices told her she would go to "France."[20] At some point, she was told specifically to go to Vaucouleurs and speak to Robert de Baudricourt, captain of the guards, who would take her to the Dauphin. By then, she was very clear on her mission, it's purpose and outcome. She told her uncle, whom she asked to introduce her to Baudricourt,

to ask him to lead her to the place where my dauphin was

because,

Was it not said that France would be ruined through a woman[21], and afterward restored by a virgin?

What "was said" was from old and recent legends and prophesies, the most recent about a woman who would don armor to save France. Joan knew of these and assumed it for herself. Again, academics will say that such prophesies are deliberately and usefully vague. Okay, a virgin savior - take your pick. But a woman putting on armor? That one was unique and directly fulfilled by Joan.[22] Her uncle went with it, and introduced her to the Captain. Joan laid it on him in full. As attested by a witness, a knight, Bertrand de Poulengy,

She said that she had come to him, Robert, on behalf of her Lord, to ask him to send word to the dauphin that he should hold still and not make war on his enemies, because the Lord would give him help before mid-Lent; and Joan also said that the kingdom did not belong to the dauphin, but to her Lord; and that her Lord wanted the dauphin to be made king, and that he would hold the kingdom in trust, saying that despite the dauphin's enemies he would be made king, and that she would lead him to be consecrated. Robert asked her who was her Lord, and she answered, 'The King of Heaven.'"

Another witness, Jean de Metz[23], a squire at Vaucouleurs, and who testified that Joan said to him,

"I have come here to the King's chamber[24] to speak to Messire Robert de Baudricourt, so that he will take me to the King or have me taken to him. And he hasn't troubled about me or my words. Nevertheless, before mid-Lent, I must go before the King even if I wear my feet off to the knees. For no kings or dukes or king of Scotland's[25] daughter or anybody else in the world can recover the Kingdom of France; there is no aid but myself although I should rather drown myself before the eyes of my poor mother, for it isn't of my estate. But it is necessary that I come, and that I do this, for Our Lord wills that I do it."

Okay, a lot going on there. Let's break it down:

- Joan clarified that she was following God ("her Lord") and God's will, not that of the Dauphin's or France;[26]

- The Dauphin should hold off any military action against the English until mid-Lent, which would be precisely when she would meet with him and organize her march on Orléans;

- She predicted here the coming advances of the English ("despite the dauphin's enemies"), who with the Burgundians subsequently launched major offenses, culminating in the siege of Orléans starting that October;

- She, Joan, herself would "lead" the Dauphin to his coronation.

Note that this occurred not only before the siege on Orléans, which she had already been told by her voices that she would liberate, but It was a month before the burning of Domrémy, which is often taken as a motive for Joan's subsequent actions.

Shortly after her return home, her village was attacked and all fled to another town, Neufchâteau[27]. It's an unclear and meaningless episode that the Court at Rouen seized upon to discredit Joan. Either she alone or with the family had lodged at an inn that served travelers, including monks, pilgrims, traveling merchants and soldiers. The owner, Jean Waldaires, "la Rousse" (redhead), was a widow, and thus the suggestion that she was either a prostitute or running a brothel. Joan testified to having helped with chores there. What does matter is that Joan's mind was not on anything but what her voices had been telling her. On her return to Domrémy, Joan told a friend,

There was a maid between Coussey[28] and Vaucouleurs who within a year would have the king of France anointed.

It was at this time that the English moved on Orléans, which, along the Loire River, was the key to the rest of France. There was at the time and has been speculation that at this time the Dauphin considered, in face of the English assault, escaping to Scotland or Spain.[29] Had Orléans fallen, this would have been a likely outcome. But it did not, so he did not.

She told her uncle Durand Laxart about it because she needed his help

Probably the first person she told about her own visions with any detail was her uncle, Durand Laxart (or Lassois), the husband of her mother's sister. Joan needed him, as he lived in the regional

Here's an example from a well documented history of the life of Joan as regards the idea that Joan was fulfilling a prophesy as silly:

Prophesies[30]

earliest visions:

"It taught me to be good, to go regularly to church. It told me that I should come into France ... This voice told me, two or three times a week, that I must go away and that I must come to France... It told me that I should raise the siege laid to the city of Orléans. The voice told me also that I should go to Robert de Baudricourt at the town of Vaucouleurs, who was the [garrison] commander of the town, and he would provide people to go with me. And I replied that I was a poor girl who knew neither how to ride nor lead in war."

I was in my thirteenth year when I heard a voice from God to help me guide my behavior. And the first time I was very much afraid. And this voice came about the hour of noon, in the summer time, in my father's garden..."

Why? Why Joan? Why her suffering?

It confounds the honest reader the betrayals, denials, and injustices that Joan suffered. It's tempting to recognize the interests and intrigues she provoked as normal reactions to the challenges to authority she presented.

Christology of Saint Joan

- born in poverty, among shepherds

- distrust of the leaders

- triumphant entry to Orleans

- betrayal

- Charles VII washing his hands of her

- championed by her mother

Joan's mission: to save France -- or Catholicism?

I have a theory. I developed it before I knew anything about Saint Joan other than she led the French to defeat the English and was burnt at the stake for it all. As I have learned more about her, the theory makes more and more sense that her mission was to save Catholicism, not France.

What is "France"?

France, as we know it, doesn't really become "France" until Philip II, but not with national integrity and full identity until Joan of Arc. It's all rather complicated, but following the Norman Invasion of England in 1066, the Normans controlled the north of France and England. After series of power grabs, political marriages, dynastic divisions, and armed contests, by the 12th century, Henry II, who spoke French,[31] had taken over a large part of western France, creating the Angevin Empire, which lasted until the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, in which the French defeated an English and a European coalition that opposed Philip II's conquests of France. As a result, English King John was severely weakened and was forced into signing the Magna Charta and Philip II consolidated France, effectively creating modern France.[32] History weaves complex, indeed.

In 1328, a succession crisis arose at the death of Charles IV of France, whose closest heir was his nephew Edward III of England. Eddie, of course, claimed the throne. Rejected by the French nobles, Ed cut a deal with the Flemish who endorsed him as King of France, everything to do, of course, with the economic binds between English sheep and Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres woolen factories. In the 1340s, Eddie put together an invasion force and in 1346 took the northern city of Caen and then thoroughly humiliated the French at Crécy, largely because the French fought the same war as at Bouvines, with heavy armor, while the English brought in the next thing, the longbow, which could be fired in rapid succession (unlike the French crossbows) and could also pierce armor from distance.

It gets complicated, what with English victories in the southwest of France (remnants of the Angevin Empire) and a series of crises in France, which led to the coronation of Charles VI, "Charles the Mad," renowned today as the crazy king who thought he was made of glass.[33] In 1420, Charles disinherited his own son, who would become the "Dauphin" (claimant to the throne of France) whom Saint Joan herself, basically, crowned as Charles VII[34], appoints the English King Henry V, who took advantage of the chaos in France and crippled the French army at Agincourt in 1415. After this, the English and their French allies ally, the Count of Burgundy, give or take some stumbles, ally for mutual benefit to take over France.

Most people would look upon the Hundred Years War as, and the language of the day, a war between the English and the French. Indeed, the French called their enemy the English, and the English called their enemy the French. In more than a small way they were all French, which is why the English king claimed the French throne.

In my theory, had the "English," whose rulers spoke French at home, won and reclaimed France on top of England, then both England and France, a hundred years later, would have under Henry VIII left the Catholic church. Sure, lots of conditions may have prevented that, but we can draw a straight line from the Church of England to the Church of England/France. This would not have pleased God.

Whatever the value of my theory that God meant to keep France Catholic, I am intrigued by this excerpt from Mark Twain's account of the trial of St. Joan:

And now, by order of Cauchon, an ecclesiastic named Nicholas Midi preached a sermon, wherein he explained that when a branch of the vine — which is the Church — becomes diseased and corrupt, it must be cut away or it will corrupt and destroy the whole vine.

Whereas the English partisan, Father Midi, saw the destruction of Joan the pruning of a dead branch of the Church (the vine, as Twain correctly explains), by cutting her off, he and Bishop Cauchon were instead pruning themselves from the vine of France. The dead vine cut off was England.

There is an additional

> Henry VIII

> to save France -- from what, the English who were French?

The prophecies of Joan of Arc

Prophecies of the coming of Saint Joan

- Merlin

- St. Bede

- Marie d'Avignon

Joan's own testimony on those prophesies

Joan told her Uncle , Durand Laxart, and a woman with whom she stayed on her second visit with him to Vaucouleurs,

“Was it not said that France would be ruined through a woman and afterwards restored by a virgin?”.

>> see Prophecies | Joan of Arc | Jeanne-darc.info

Testimony of Brother Séguin de Séguin of four of Joan's prophesies

The Dominican friar participated in the inquiry into Joan ordered by the Dauphin after she presented herself to the Court at Chinon. The priest was a Professor of Theology and well-respected. He later testified that she made four prophesies

- Orléans would be liberated from the English

- the King would be crowned at Rheims (which

- Paris would liberated from the English

- the Duc d'Orléans (Duke of Orleans) would be freed from imprisonment in England

That last prophesy was significant because, while no more improbable than the others, it occurred ten years after her death and had the Duke[35] not returned to France he would never have fathered Louis of Orléans who was crowned Louis XII, King of France, in 1498.

Joan insisted upon the coronation of Charles VII at Rheims, which seemed not ridiculous but dangerous, Rheims was in Burgundy, held by the English allies under the Duke of Burgundy. After Orléans, Joan insisted upon the necessity that the coronation be held in Rheims, which was where Philip II, creator of modern France, was crowned, and was the site of the baptism of Clovis.

From Fr. Séguin's testimony:

I saw Jeanne for the first time at Poitiers. The King’s Council was assembled in the house of the Lady La Macée, the Archbishop of Rheims, then Chancellor of France, being of their number. I was summoned, as also were [list of names] ... The Members of the Council told us that we were summoned, in the King’s name, to question Jeanne and to give our opinion upon her. We were sent to question her at the house of Maître Jean Rabateau, where she was lodging. We repaired thither and interrogated her. And then she foretold to us—to me and to all the others who were with me—these four things which should happen, and which did afterwards come to pass: first, that the English would be destroyed, the siege of Orleans raised, and the town delivered from the English; secondly, that the King would be crowned at Rheims; thirdly, that Paris would be restored to his dominion; and fourthly, that the Duke d’Orléans should be brought back from England. And I who speak, I have in truth seen these four things accomplished.

Liberating Orleans

Freeing the Duke of Orleans

The Crowning of Charles VII

The end of the Hundred Years War

Why Joan only now?

Jeanne d'Arc was canonized in 1905. It's not unusual for such a long delay in beatification, but there are reasons for it with Saint Joan. So why so long for her?

Once her work was done, she was easily forgotten, beginning with the Siege of Orleans and the coronation of Charles VII, upon which the French court did its best to ignore her. Given the opportunity to ransom her upon her capture, the King refused and, well, washed his hands of her. Once they had consolidated rule over France, the kings had every reason -- well, aside from honesty -- not to attribute the legitimacy of their rule to a peasant girl.

>

A rather interesting document is found from a publication, "The Rationalist" from 1913, The Story of Joan of Arc: the Witch Saint,"[36] which seems to have been in response to Pius X's beatification of Joan (final step towards canonization). The author contends that "modern thought" has led to her vindication and not the Catholic Church, which is just using her shrine and stories of miracle cures before it as a "new income." The author says his essay will save Catholicism from itself.

French Revolution

> anticlerical

>

Franco-Prussian War

Historical sources

The history of Joan of Arc is comparatively well-documented, even for the 1400s, a period that yields plenty of artifacts and primary sources. The facts of her life a clear and incontestable. In her day, she was the subject of various documented inquiries, an extended court trial, and subsequent inquiries that document witnesses and assessed evidence. We even know much about her mystical experiences -- or whatever they were, as she told the record about them.

The Trials of Jeanne d'Arc

> see Trials - Overview | Joan of Arc | Jeanne-darc.info

Books on Saint Joan of Arc

A word on modern Joan of Arc historiography

You will find in the below review of Mark Twain's biography of Joan mention that Twain has been accused of obsessing over little girls and thus his study of Joan of Arc is infatuation not art, a tainted, shall we say, yucky, take on her story. Not at all! Nonetheless, St. Joan somehow challenges the gender-obsessed 20th and 21st centuries. There is absolutely nothing to consider regarding that she was burned as a witch for having worn men's clothing. It had nothing to do with 15th century gender identity. She was a soldier, and soldiers wear pants and cutting her hair, if she did, was an act of prudence not some transgender identity. So we have today works, websites and popular conceptions of Joan as a modern, sexually unburdened, liberated woman. So when you go looking for information about Joan, look carefully, as the perspectives and agenda reveal themselves, such as non-religious, girl-power[37], or gay[38] perspectives.

So be careful.

In addition to author agenda and bias, the various biographies or histories, you will find many discrepancies in the facts and timelines provided. The problem is twofold:

- The record of the Trial at Rouen is subject to reasonable interpretation, as it was deliberately edited by the Court to put Joan in a bad light. The main stenographer was loyal the record, but even his manuscript was subject to change. Additionally, we have only copies of those transcripts, so those are subject editorial abuse, as well. This is not to say that the transcripts are false and ahistorical -- they are a uniquely complete testimony of an historical event. We just need to be careful with it.

- The various testimonies at the Trial at Rouen and the later Rehabilitation Trial may have conflicting eye witness testimony. That, too, is not irreparable as an historical record, it just means that the historian needs to make choices. More difficult, though, is that the timeline gets confusing as the testimony does not follow chronology. In other words, various witnesses may testify to the same event or moment, but their testimony is scattered across the record, not presented linearly.

So it is best to use various sources and compare them constantly, making up your own mind as to the most accurate.

Annotated bibliography

I'm not yet sure of the perspective of the author of this site, but he has produced a useful bibliography with "comments" (annotations): https://joan-of-arc.org/ls_bibliography.html#joa_pernoud

Accounts of the life of Joan of Arc

Recollections of Joan of Arc by Mark Twain

Few people know that Twain wrote about Joan of Arc. There is a story that as a child he encountered a stray page with the story of her trial, and the young Samuel Clemens took great offense at her interrogators. Whether true or not, he became fascinated by her story and yearned to tell it:

I like Joan of Arc best of all my books; and it is the best; I know it perfectly well. And besides, it furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.[39]

Modern academics who study Twain consider it unworthy of his canon.[40] They can't deny that he thought it was his greatest work, and also that it contains classic Twain wit, but they just can't stand that he was "infatuated" with the Maiden of Orleans.

Some critics complain that in writing the book, Twain succumbed to Catholicism. I have no words to express how stupid that is. It's got to be their animosity for Christianity in general, and for Catholicism in particular, when expressed as profoundly by Saint Joan. Worse, one actually claims that Twain was infatuated by cross-dressing (such as one hilarious scene in Huck Finn and two examples from minor short stories[41]) and his interpretation of the trial of Joan was entirely focused on her male dress. It's even stupider than the accusation of Twain as overly Catholic.

As for Twain's Catholicism, let's just say he falls short. Across this narrative of the life of a devout Catholic, he says next to nothing of the Mother of God, whereas the historical record affirms Joan's devotion to Our Lady.[42] Twain mentions but fails to illuminate the crucial role of Joan's despair over denial of the Sacraments in her coerced "abjuration" (a kind of renunciation, but short of full admission) seven days before her execution. Her longing for the Eucharist must have pained her as much as any other injustice she suffered, and one can be sure that Luke 2:34, "(and you yourself a sword will pierce)" was her regular companion. There are other examples, but none detract from Twain\'s marvelous work. I mention it to show how idiotic it is to criticize Twain for succumbing to either Catholicism or Medieval mysticism, or that he was infatuated with transvestitism - a shameful accusation[43]!

Twain indeed fell in love with the story of Joan of Arch, and he dedicated himself to telling it. And not wonder he worked so hard on it: it's not an easy story to tell, and the lines he draws between his fictionalized characters and the true history are narrow, while never leading the reader astray from actual events. It's a grand project.

A final note: Twain wrote the book before Joan was canonized, thus "Saint Joan" does not appear in the work. Twain does describe her as a saint:

She was not solely a saint, an angel, she was a clay-made girl also — as human a girl as any in the world, and full of a human girl's sensitivenesses and tendernesses and delicacies.[44]

Saint Joan by George Bernard Shaw

Not much to say about this one. Shaw was early in adulthood an atheist and seems to have wanted into Deism and perhaps belief if not in Christ but in Jesus. The play is considered one of Shaw's greatest works, and it has been repeated on stage through the 2000s and in film. Shaw wrote it after Joan's canonization, thus the title. But he wasn't celebrating it. He tries to humanize Saint Joan, whom he said was romanticized while her accusers were villainized. For Shaw, Joan's tormenters were motivated by the facts and situations before them; you know, it's just a matter of perspective. I can only say that to frame Bishop Cauchon as honestly motivated is akin to Andrew Lloyd Weber's sympathetic portrayal of Judas in Jesus Christ Superstar. Both did wrong, knew it, and did it anyway. And, worse, Shaw portrays Joan as Weber does Jesus, as an anti-establishment pop star. For Shaw, Joan is a rebel against authority, like his female ubermensch in Man and Superman. Meh.

Jeanne D'Arc (1895) by Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel

In 1896, Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel illustrated a children's book of the life of Joan of Arc.[45] Through the early 1900s, he expanded several of the images into full paintings, a collection of which are held by the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, called "La Vie de Jeanne d'Arc":

-

La Vision (Vision of the Archangel St. Michael)

-

Appeal to the Dauphin (the Dauphin had someone else sit on the throne and hid amidst the Court; Joan identified him immediately)

-

The Maid in Armor on Horseback (now Commander of the French Armies, Joan marches the army to free Orleans from the English siege)

-

The Turmoil of Conflict (the Battle of Orleans, which is nearly lost after Joan is hit in the shoulder and neck by a bolt, but she returns to the field and leads the French to victory)

-

The Crowning at Rheims of the Dauphin (Joan's mission was to have the Dauphin properly crowned King by French custom and in the form of Charlemagne; the leadership thought it was unnecessary, but Joan understood that the people of France needed the ceremony)

-

The Trial of Joan of Arc (The King and his councilors betray Joan, leaving her to fight with a small army; she is captured by the French ally of the English. The French King refuses to pay a ransom for her, and she is tried in an illegitimate ecclesiastic court)

Boutet de Monvel first prepared his work on Joan for a children's book, a genre in which he is recognized as significant.[46] The book was a sensation, and he was commissioned to paint similar images as large murals at the newly built Basilica of Donrémy, Joan's birthplace. Only one panel was completed, but William Clark, of a great Montana copper mining fortune, commissioned smaller versions, of which Boutet de Monvel completed six. Clark arranged for his entire art collection, including the Joan of Arc panels to be donated to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC (constituting the entire "Clark Wing" of the building), upon Clark's death. Clark, of Scotch-Irish and French Huguenot descent, was a Presbyterian. His Montana business and political rival was a Catholic, Marcus Daly, and whose investor, Henry Rogers loathed Clark, spurring a 1907 rant against Clark by, ironically in light of his Joan of Arc fascination, Mark Twain. Clark's second wife, neé. Anna Eugenia La Chapelle, was possibly the source of his own interest in Saint Joan. Anna was a French Canadian Roman Catholic, and she had married in Paris. He was an avid art collector

- ↑ She thus introduced herself to the Dauphin, ruler of France.

- ↑ Joan of Arc : her story, p. 221

- ↑ Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality : Gies, Frances (archive.org) places the first use of the name d'Arc in 1576 (p. 10).

- ↑ Academics argue that pucelle come form the Latin puella for "girl" or "servant girl" and without any connotation of virginity. Joan's virginity was essential to her mission both as sign of purity and, more importantly, selfless dedication to the Lord. They might try 1 Corinthians 7:34: "An unmarried woman or a virgin is anxious about the things of the Lord, so that she may be holy in both body and spirit."

- ↑ He ordered her execution by a torture machine, "the wheel," which would have the effect of being drawn and tortured; but each machine brought to her fell apart upon her touch, so he had them cut her head off. Instead of blood, a milky white fluid poured from her neck.

- ↑ See Catherine of Alexandria, Saint | Catholic Answers Encyclopedia which discussed the exaggerated stories attributed to Saint Catherine by medieval hagiographers. The Wikipedia entry on Saint Catherine flatly states that she probably never existed.

- ↑ Translation: "A great blow upon your people that was assembled there [at Orleans] in great number, caused in large part, as I believe, by lack of firm faith, and unlawful doubt that they had of a disciple and limb of the devil, called the Maid, who used false enchantments and sorcery. This blow and defeat not only diminished in large part the number of your people." Original text from Joan in her own words, p 223

- ↑ The two Houses were at war with one another, with the House of Orléans siding with the French and the House of Burgundy the the English. (That latter alliance nearly broke apart with the Burgundians signing a mutual defense treaty with the Dauphin, but the English restored the alliance by 1425.) The Armagnac-Burgundian civil war started over a lovers' spat or spat of jealousy that ended with the assassination of the Duke of Orléans, Louis I. The English took advantage of the turmoil, as well as the weakness of the French King, Charles VI, "the mad" (as in insane, and he was), and invaded France, crushing them at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Things were nominally settled in 1420 in the Treaty of Troyes, which named the English King, Henry V the royal successor of the French King Charles VI -- and disinheriting his son, the Dauphin Charles. The Dauphin, however, organized French loyalists to dispute the Treaty, and so left the country with English control of Northern France, the Dauphin's control of central-southern France, and their respective allies with other areas in and around those two larger powers, especially in the eastern region where Joan grew up.

- ↑ The source and very upper reaches of the Meuse was in Lorraine, which was nominally bound to the Holy Roman Empire and did not take part in the latter parts of the 100 Years War. The lower Meuse was controlled by the Burgundians.

- ↑ The commander there, Robert de Buadricourt, after two attempts by Joan, agreed to send her with some soldiers to meet the Dauphin at Chinon.

- ↑ One skeptical historian called hers "a prosperous peasant family," lol. See Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality : Gies, Frances (archive.org)

- ↑ Jacques provides a textbook example of a peasantry beneficiary of the prior century's Black Death, which empowered the peasantry through the drastic reduction in population.

- ↑ Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality : Gies, Frances (archive.org) p. 9

- ↑ See Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality : Gies, Frances (archive.org) p. 21

- ↑ Lives of the Saints, by Alban Butler, Benziger Bros. ed. [1894], This is one of the first versions of Lives of Saints, which were widely distributed in 15th and 16th Century England, to include an entry on Joan. Let's say the English did not celebrate her back then...

- ↑ Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality : Gies, Frances (archive.org); p. 20

- ↑ Mark Twain embellished the importance of this tree, as have others. In actuality, the village celebrated two festivals related to springs near it, Laetare, Jerusalem, during Leny, and May Day. The tree was a common spot for villagers who often gathered by it.

- ↑ The virgin with a banner was supposedly prophesized by the English magician Merlin. That of the armed virgin, however, was recent, coming in 1398 from Marie Robine and included a vision that those who refuse to believe divine visions are idolaters, among which were theologians at the University of Paris -- the same who were involved in the trial of Joan. See Marie Robine - Wikipedia

- ↑ See Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality p. 28: "Whatever the source of Joan's voices and her belief in them, it conferred on her a strength of resolution possessed by few, women or men." Ugh.

- ↑ Recollecting that Domrémy was not under direct control of the French Dauphin.

- ↑ A reference understood then, and maknig the most sense now, to the mother of the Dauphin, the wife of Charles VI, Isabeu of Bavaria, who stood as regent during her husband's episodes of madness, and who took part in the machinations that led to the Treaty of Troyes, which gave royal succession to the English King Henry V over he own son, Charles the Dauphin.

- ↑ Look it up: a few women across history and time donned armor or weapons and fought like, with and against men. None led an army as did Joan, and none wore full plate armor.

- ↑ Listed in the Rehabiltation Trial as "Jean de Nouvilonpont" (p. 393)

- ↑ By "chamber" she means representative of or place belonging to the King, not a room in his house.

- ↑ Earlier in the War, A Scottish force came to aid France but was destroyed in Battle.

- ↑ That the Dauphin would "hold the kingdom in trust" is revealing and indicative of her mission: God's will and not just glory to France. What she says here upholds my idea that her mission was to save France to save Catholicism, not just to save France.

- ↑ There seem to have been two stays with la Rouse, but It doesn't really matter except as to the Rouen Court's use of it to try to discredit her. I'm thinking there was only one in July 1438.

- ↑ A village just south of Domrémy, on the way towards Neufchâteau.

- ↑ See Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality pg 43

- ↑ Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality : Gies, Frances : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : (archive.org), p. 30

- ↑ Henry IV, crowned in 1399, was the first English king of the Norman period to speak English natively. Passed under the French-speaking Henry III, the 1362 Statute of Pleading made English the official language. Since the English by then had lost most of their holdings in France, Henry III needed to embrace an English national identity.

- ↑ His predecessors were Kings of the Franks; Philip II was the first to declare himself King of France.

- ↑ He is supposed to have had iron rods sewn into his gown to keep himself sturdy and not break. His psychoses manifested in various other ways, including to forget who he was or those around him and to run around the palace hysterically. Up until the late Biden presidency, I might have used the situation as an example of the insanity of monarchy, as why'd they keep the crazy man in power? Well, as with the incompetent Joe Biden, those in power around him depended on the King's title for their own power. We will see how this dynamic impacts Saint Joan.

- ↑ In words she led him to the coronation

- ↑ The title Duke of Orleans was like that of Prince of Wales, indicating the heir to the throne. Louis, Duc d'Orléans was the brother of King Charles VI, father of Charles VII, the Dauphin in the story of Saint Joan. It's a bit complicated, but rule of France was broken up by faction and the insanity of its King who disinherited his son the Dauphin and gave France to the English King Henry V. Though crowned at Paris by Charles VI as heir, Henry, needed to actually control France, which he did not adn could not accomplish before he died. His son was a child who inherited the claim as King of France, but there was no meaning to it once Joan had the Dauphin crowned at Rhiems and when, subsequently, the English were finally defeated later on.

- ↑ The Story of Joan Of Arc the Witch--saint, by M. M. Mangasarian

- ↑ See The trial of Joan of Arc : Joan, of Arc, Saint, 1412-1431 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming (Archive.org)

- ↑ This essay seeks "gay icons" of Saint Joan: What Did Jeanne d'Arc Look Like?: "GLBT historians love to claim Jeanne as lesbian, bisexual or transgendered. I’m one of those who think she was a case of androgen insensitivity syndrome — burned at the stake in 1431 for her “crime” of flouting Catholic rules on gender and women’s clothing."

- ↑ Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc - Wikipedia No source is given for the quotation, but it is undoubtedly Twain's words.

- ↑ See Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc - Wikipedia

- ↑ The Riddle Of Mark Twain’s Passion For Joan Of Arc | by The Awl | The Awl | Medium

- ↑ See The Virgin Mary and the “Voices” of Joan of Arc | SpringerLink

- ↑ The author of The Riddle Of Mark Twain’s Passion For Joan Of Arc references another academic who points to Twain\'s correspondence with young girls, which apparently embarrassed Twain\'s daughter at some point -- yet even that source admits Twain of no improprieties.

- ↑ citation to do >> p. 369 of 1901 edition (not in Harpers)

- ↑ Scan of English version (abbreviated from the original French publication) available here: Joan of Arc : Boutet de Monvel, Louis Maurice, 1850-1913 (Archive.org) Here for page images of the original: Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel

- ↑ His ability to avoid unnecessary details and focus on content is considered the core of his skill as illustrator. The works, themselves, are a tremendous artistic accomplishment. See Biography: Maurice Boutet de Monvel

Sources

working sources:

Current:

- Joan of Arc : the legend and the reality : Gies, Frances (archive.org)

- Joan of Arc - Poitiers Testimony\

- Joan of Arc Biography - Visions

- Joan of Arc - Maid of Heaven - Vaucouleurs Where Joan's Mission Began

Wikipediag

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joan_of_Arc#Chinon

- Siege of Orléans - Wikipedia

- Charles VII of France - Wikipedia

- Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War - Wikipedia

Other:

- https://joan-of-arc.org/ls_bibliography.html#joa_pernoud

- Joan of Arc: Her Prophecies (saint-joan-of-arc.com)

- The origin of Jeanne's voices and visions (jeanne-darc.info) and Visions | Joan of Arc | Jeanne-darc.info

- Visions | Joan of Arc | Jeanne-darc.info

- Materials on Joan of Arc (iu.edu)

- At Her Trial, St. Joan of Arc Faced Her Accusers Alone| National Catholic Register (ncregister.com)